Long before the invention of banks and digital wallets, human civilizations relied on something more personal and immediate that is trust. Thousands of years ago, trade was simple:a farmer may exchange a bushel of wheat for a pair of shoes from a shoemaker. This system, part of Islamic Finance which was built on mutual need and direct exchange. But as societies grew and trade expanded, this revealed its trust limitations—what if the shoemaker didn’t need wheat that day?

Among these systems, Islamic Finance stands out not only for its longevity but also for its commitment to ethics. Rooted in principles back over 1,400 years to the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), Islamic finance represents money not just as a tool for wealth, but as a means of justice, balance, and social equity. In a modern world which is driven by profit , here Islamic finance offers a refreshing alternative that replaces money with serving people.

1. Introduction

Islamic Finance is not merely a religiously compliant financial system—it is a moral, ethical, and economic framework rooted in justice, fairness, and mutual benefit. Originating in 7th-century Arabia under the guidance of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him), Islamic finance emerged as a transformative system that redefined the norms of trade and commerce in a society deeply immersed in economic injustice, exploitation, and financial inequity. While today Islamic banking and finance is a global industry valued in trillions of dollars, its origins trace back to the foundational principles laid down during the Prophet’s era, when money was not just a medium of exchange but a tool of empowerment and social equity.

The Prophet himself engaged in trade as a young man, working under the successful businesswoman Khadijah (RA), who would later become his wife. His integrity and transparency in business dealings set a new ethical standard, earning him the titles Al-Amin (the Trustworthy) and Al-Sadiq (the Truthful). His personal involvement in commercial practices provides the earliest recorded examples of Islamic financial ethics in action. As Islam spread, these values became embedded in legal rulings (fiqh) and institutional structures, including the development of financial contracts like mudarabah (profit-sharing), musharakah (joint ventures), and murabaha (cost-plus sales). These models emphasized partnership, risk-sharing, and real asset-backed transactions—offering a clear alternative to riba-based systems.

2. Pre-Islamic Arabian Trade Practices

To fully appreciate the transformative nature of Islamic finance, it is essential to first understand the economic and commercial environment of Arabia before the advent of Islam. The Arabian Peninsula—particularly Mecca—was a prominent center for trade and commerce, strategically located between the Byzantine and Persian empires. Despite this commercial vibrancy, the region’s financial system lacked ethical structure, resulting in widespread exploitation, inequality, and systemic injustice.

2.1 The Economic Landscape

The economy of pre-Islamic Arabia was primarily based on barter trade, where people exchanged goods such as dates, wheat, camels, and textiles in the absence of standardized currency. Although gold dinars and silver dirhams—imported from Byzantine and Persian sources—were in circulation, day-to-day transactions largely relied on the direct exchange of goods, often leading to disputes over value, quality, and timing.

Mecca emerged as a commercial hub due to the spiritual and cultural significance of the Kaaba, which attracted pilgrims and traders from across the region. The Quraysh tribe, which controlled Mecca, played a dominant role in both local and international trade. They organized major caravans to Yemen in the winter and Syria in the summer, trading high-value goods such as spices, perfumes, leather, and textiles—turning Mecca into a vital node in Arabia’s trading network.

2.2 Business Practices and Financial Exploitation

Despite its economic dynamism, trade in pre-Islamic Arabia was marred by deep-rooted injustices. One of the most exploitative practices was riba (usury)—the charging of excessive interest on loans. Wealthy lenders used riba to trap the poor in perpetual debt. Those unable to repay were often enslaved, or forced to forfeit property or labor, perpetuating cycles of poverty and humiliation. Another unethical practice was gharar (excessive uncertainty) in trade contracts. It was common to sell goods that didn’t yet exist, hide product defects, or obscure terms of sale.

Traders frequently cheated with weights and measures, and there was no enforceable mechanism to protect buyers from deception. Furthermore, monopolies and hoarding were used to artificially manipulate market prices. Powerful merchants would withhold essential goods during shortages to inflate prices—causing hardship among the general population. With no legal or ethical oversight, the strong preyed on the weak, and business was driven purely by greed and power.

2.3 Social Consequences

The absence of ethical financial principles created a deeply stratified society. A small elite, particularly within the Quraysh tribe, hoarded wealth, while the majority struggled in poverty. There was no recourse for debtors, no legal protections for the exploited, and no social safety nets. The result was a society teeming with economic frustration and moral decay.

Women were among the most affected. They were largely excluded from economic participation, lacked property rights, and were often treated as objects or part of inheritance. The absence of justice in commercial dealings was reflected in broader social oppression and inequality.

2.4 The Need for Reform

This unjust and exploitative environment created an urgent demand for moral and structural reform. Islam’s arrival was not only spiritual—it brought a revolution in economic ethics. The Qur’an, revealed to Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), directly addressed Meccan society’s financial injustices. It outlawed riba, prohibited gharar, emphasized fair trade, honesty, and mutual consent, and demanded protection for the poor and vulnerable.

The Islamic financial model introduced principles that aimed to establish social justice, equity, and economic dignity. The stark contrast between pre-Islamic practices and the values promoted by Islam highlights the transformative nature of the new system. What followed was not a minor reform—but a complete shift from exploitation to ethics-based commerce that sought long-term prosperity for all.

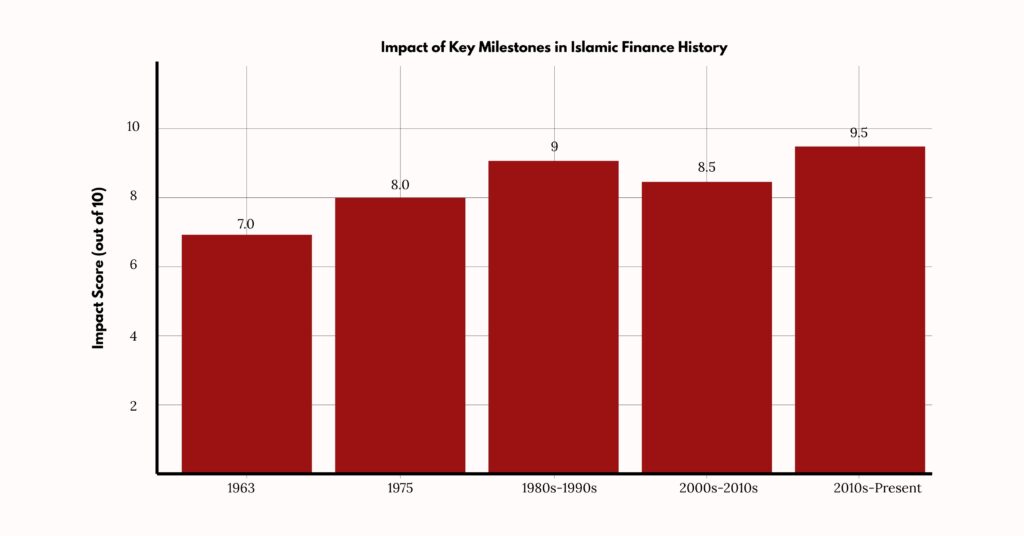

3. Financial Ethics Introduced by Islam

When Islam emerged in 7th-century Arabia, it was not only a spiritual and social revolution but also an economic one. The revelations of the Qur’an and the actions of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) introduced a framework of financial ethics that directly challenged the exploitative norms of pre-Islamic commerce. Islamic finance, at its core, is not merely a set of financial contracts—it is an ethical system grounded in justice, transparency, and accountability. The aim was not only to regulate business transactions but to ensure that economic activities contributed to social welfare and human dignity.

3.1 Prohibition of Riba (Interest)

One of the most transformative reforms in Islamic finance was the strict prohibition of riba, or usury. The Qur’an explicitly denounces riba in several verses:

“Allah has permitted trade and has forbidden riba…” (Surah Al-Baqarah, 2:275)

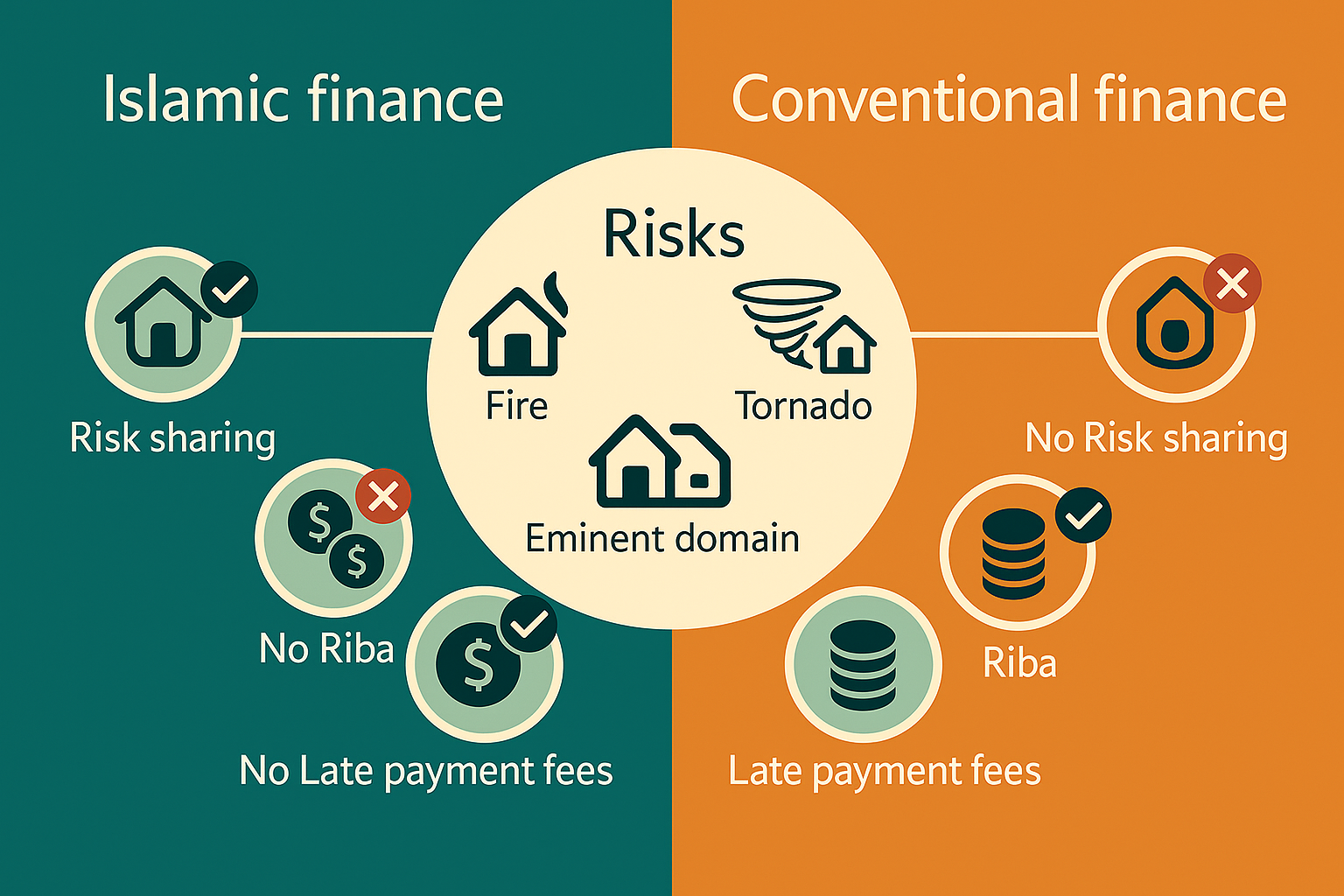

In pre-Islamic Arabia, riba was a common tool of exploitation, enabling the rich to grow wealthier at the expense of the poor. Islam outlawed this practice, considering it oppressive and unjust. Instead of earning money through guaranteed, risk-free interest, Islam encouraged earning through productive investment and shared risk.

This ethical shift paved the way for Shariah-compliant financial contracts such as:

- Mudarabah (profit-sharing between investor and entrepreneur)

- Musharakah (joint investment partnerships)

These models emphasized risk-sharing, effort-based returns, and cooperative ventures, fostering a more equitable financial system.

3.2 Promotion of Fair Trade

Islam places great emphasis on fairness and honesty in trade. The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) said:

“The truthful and trustworthy merchant is with the Prophets, the truthful, and the martyrs.”(Hadith – Tirmidhi)

Merchants were encouraged to avoid deception, false advertising, and misrepresentation. Any form of cheating—whether in weights, measures, or product quality—was strongly condemned. The Qur’an warns:

“Woe to those who give less [than due], who when they take a measure from people, take in full. But if they give by measure or weight to them, they cause loss.” (Surah Al-Mutaffifin, 83:1–3)

These verses not only emphasize transactional fairness but also aim to build trust between buyer and seller, which is essential for a healthy economy.

3.3 Condemnation of Gharar (Excessive Uncertainty)

Another core ethical principle introduced by Islam was the prohibition of gharar, which refers to excessive uncertainty, ambiguity, or speculation in business contracts. Deals based on unknown outcomes, vague terms, or speculative risks were considered unfair and were discouraged.

Practices of gharar include:

- Selling goods not in one’s possession

- Undefined delivery timelines or payment terms

- Highly speculative investments

The aim was to ensure that all financial transactions were based on clarity, transparency, and mutual consent. This prevented manipulation and safeguarded both buyers and sellers from unjust losses, laying the groundwork for ethical contractual practices still upheld in modern Islamic finance.

3.4 Encouragement of Risk Sharing and Mutual Benefit

Islam encourages economic systems where both profit and risk are shared, leading to fairness and collective growth. Contracts like mudarabah (profit-sharing) and musharakah (joint venture) are based on this philosophy. Unlike interest-based systems, where lenders earn regardless of outcome, Islamic finance ensures that both parties succeed or fail together. This not only reduces inequality but fosters collaboration and entrepreneurship.

3.5 Wealth Circulation and Social Welfare

Islamic finance emphasizes that wealth should circulate within society and not remain concentrated in the hands of a few. The Qur’an instructs:

“…so that it will not be a perpetual distribution among the rich from among you.” (Surah Al-Hashr, 59:7)

To ensure this, Islam introduced mandatory and voluntary forms of charitable giving, such as:

- Zakat (obligatory alms): A fixed portion of wealth given to the poor annually.

- Sadaqah (voluntary charity): Encouraged as an act of piety and compassion.

Moreover, hoarding wealth or assets without productive use or benefit was discouraged. Islamic finance therefore links economic activity with moral responsibility, promoting an inclusive financial system where the needs of the poor, orphans, and the marginalized are addressed.

4. Business Models in the Prophet’s Time

During the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), several business models were developed or refined under Islamic principles to ensure that trade was not only profitable but also ethical and socially just. These models provided alternatives to interest-based and exploitative systems, emphasizing transparency, mutual consent, risk-sharing, and fairness. Below are the key business and financial models practiced during his time, along with examples and their socioeconomic impact.

4.1 Mudarabah (Profit-Sharing Partnership)

Mudarabah is a partnership where one party provides capital (rabb-ul-maal) and the other provides expertise and labor (mudarib). Profits are shared according to a pre-agreed ratio, while losses are borne only by the capital provider, unless there is negligence by the manager.

Example:

Before prophethood, Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) himself engaged in a mudarabah agreement with Khadijah (RA), a successful businesswoman. She provided the capital, and he managed trade caravans to Syria and Yemen. His honesty and efficiency resulted in significant profits, leading to their later marriage.

Impact:

- Empowered women like Khadijah (RA) to participate in commerce without physical involvement.

- Reduced unemployment, as skilled but capital-less individuals could engage in business.

- Promoted economic growth through trust and mutual benefit.

- Laid the groundwork for Islamic venture capitalism, enabling entrepreneurial activity without debt traps.

4.2 Musharakah (Joint Venture Partnership)

Musharakah is a partnership in which all parties contribute capital and share in both profits and losses, based on their investment proportion or a mutually agreed ratio.

Example:

In the early days of Medina, Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) encouraged Ansar (Medinan Muslims) and Muhajirun (Meccan migrants) to partner in business activities. For instance, agricultural lands, trade routes, and date farms were used in joint ventures where both labor and capital were shared.

Impact:

- Promoted community bonding and economic solidarity between different social groups.

- Minimized inequality through shared ownership and joint decision-making.

- Reduced reliance on loans or credit, instead fostering risk-sharing.

- Created resilient local economies based on cooperation rather than competition.

4.3 Murabaha (Cost-Plus Sale)

Murabaha is a sale contract in which the seller discloses the actual cost of the product to the buyer and adds a clearly defined profit margin. This model ensures transparency, mutual consent, and avoids interest, making it widely used in Islamic finance even today.

Example:

While not labeled “Murabaha” in early Islamic texts, the practice was clearly applied. For instance, a trader might purchase a commodity like cloth for 10 dirhams and sell it with full disclosure for 12 dirhams. The Prophet (PBUH) encouraged such honesty in pricing.

He said: “The seller and the buyer have the right to keep or return goods as long as they have not parted. And if they spoke the truth and made clear the defects of the goods, then they would be blessed in their transaction.”

(Sahih al-Bukhari)

Impact:

- Built trust between buyer and seller through full price disclosure.

- Encouraged small-scale merchants to grow businesses without deception or interest-based loans.

- Offered a stable and ethical alternative to high-interest consumer loans.

- Became a cornerstone of Islamic retail finance, especially in asset-backed transactions (like selling homes, electronics, or vehicles).

4.4 Salam (Advance Payment Contract)

Salam is a forward contract where the buyer pays the full price in advance for goods that are to be delivered later. It was introduced to support farmers and producers in need of capital before harvest.

Example:

In Medina, many farmers needed money for seeds, tools, and labor but had no income until the harvest. Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) allowed salam contracts, where traders paid upfront for future delivery of dates, wheat, or other crops. However, the product, quantity, quality, and delivery date had to be precisely defined, eliminating ambiguity (gharar).

He said: “Whoever pays in advance for dates (to be delivered later) should do so for a specified measure, weight, and time.”

(Sahih al-Bukhari, 2239)

Impact:

- Helped small farmers avoid riba-based debt while still accessing necessary capital.

- Boosted agricultural productivity by ensuring pre-season funding.

- Provided a Shariah-compliant model of pre-order financing—a precursor to today’s forward contracts in Islamic economics.

- Encouraged clear contract writing and mutual responsibility between producers and buyers.

4.5 Ijara (Lease-to-Use or Lease-to-Own)

Ijara is a leasing contract where one party leases an asset or property to another for a specified rent and period. Ownership remains with the lessor while the lessee gains the right to use the asset. The lease may include an option for the lessee to own the asset eventually.

Example:

During the Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) time, leasing was a common practice for agricultural land and livestock. For instance, a farmer might lease land from a landowner for a season, paying rent either in cash or a share of the produce. This practice avoided land sales that could disenfranchise poor farmers, while providing them access to resources.

Impact:

- Access to productive assets: Ijara allowed those without capital to use land, tools, or animals, facilitating income generation without upfront ownership.

- Risk management: Since ownership remained with the lessor, risk related to ownership and maintenance was shared, reducing economic vulnerability.

- Wealth distribution: By leasing instead of outright selling, wealthier landowners maintained stable income while empowering tenants.

- Modern relevance: Ijara has evolved into Islamic leasing and hire-purchase models used widely in Islamic banking for homes, vehicles, and equipment.

4.6 Waqf (Charitable Endowment)

Waqf is a voluntary, permanent charitable endowment of property or assets for religious or social purposes. The asset’s ownership is donated in perpetuity, and its benefits are used to serve the community, such as funding schools, hospitals, mosques, or welfare projects.

Example:

During the Prophet’s lifetime, establishing waqf was encouraged as a form of social solidarity. A notable example is the public wells and water reservoirs in Medina that were maintained through waqf to ensure free water access for all, particularly the poor and travelers.

Impact:

- Social welfare: Waqf provided sustainable funding for public goods and services, reducing government burden and promoting community self-reliance.

- Economic stability: It prevented the concentration of wealth in private hands by dedicating assets to community use.

- Encouraged philanthropy: Muslim society was inspired to use wealth for lasting good, reinforcing the moral duty of wealth redistribution.

- Legacy: Waqf institutions have historically funded education, healthcare, and infrastructure in the Muslim world and remain important to this day.

4.7 Kafalah (Guarantee)

Kafalah is a contract of guarantee where one party assumes responsibility to fulfill the obligations of another in case of default. It is a form of suretyship ensuring that debts or commitments are honored, enhancing trust in financial dealings.

Example:

In the Prophet’s time, personal reputation and social bonds were vital. For example, if a merchant lacked sufficient collateral, a trustworthy companion could act as a kafil (guarantor), assuring repayment or delivery. This practice reduced risk and encouraged commerce.

The Prophet (PBUH) said: “He who is made a guarantor for a debt, and he pays it, will have reward as if he had spent that amount himself.”

(Hadith – Abu Dawood)

Impact:

- Enhanced creditworthiness: Kafalah helped individuals or traders without assets secure financing by relying on social trust.

- Strengthened community ties: It promoted collective responsibility and social cohesion.

- Reduced financial exclusion: Allowed those with limited capital to participate in trade and business.

- Basis for modern Islamic credit guarantees: Contemporary Islamic banks use kafalah to back loans, minimizing risk while adhering to Shariah.

4.8 Qard Hasan (Benevolent Loan)

Qard Hasan is an interest-free loan extended for welfare purposes or urgent needs, where the borrower repays only the principal amount. It embodies the spirit of charity, generosity, and social solidarity.

Example:

Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) encouraged lending without interest to assist the poor and needy. For instance, during times of hardship, Muslims were urged to provide qard hasan to help those unable to meet basic needs, expecting repayment without profit.

He said: “Whoever grants a Qard Hasan to his brother to pay off his debt, Allah will write for him a reward as if he had set free a slave.”

(Hadith – Tirmidhi)

Impact:

- Social safety net: Qard hasan functioned as a support system preventing exploitation by moneylenders charging exorbitant interest.

- Economic inclusion: Provided capital to small traders, farmers, and families in distress.

- Moral economy: Reinforced altruism and discouraged profiteering on others’ hardships.

- Contemporary role: Islamic microfinance and social welfare programs often incorporate qard hasan schemes to uplift marginalized communities.

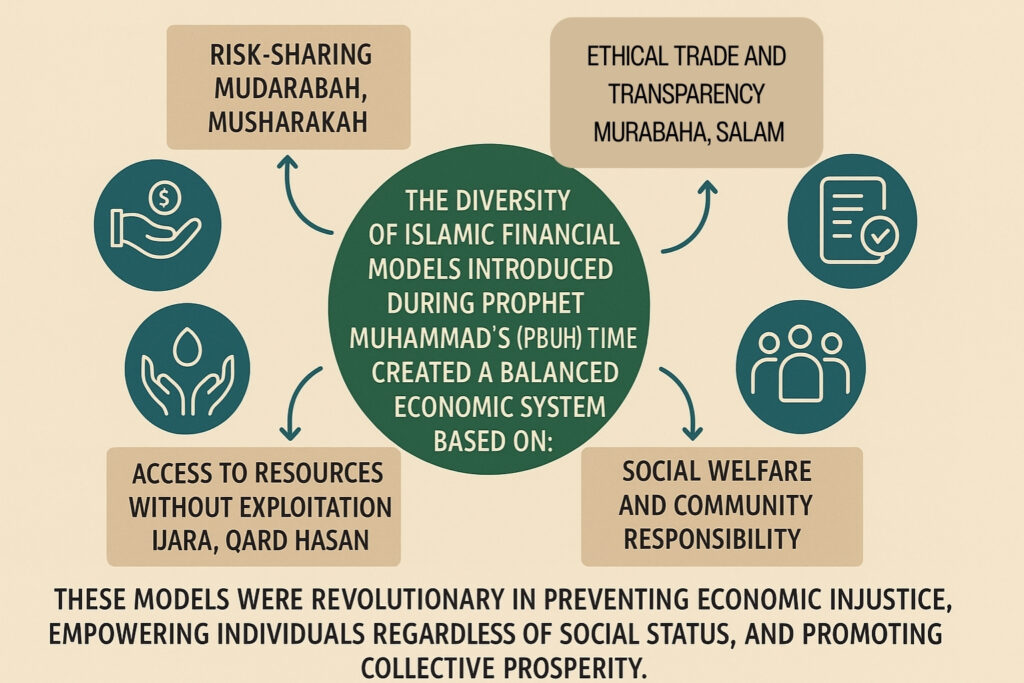

The diversity of Islamic financial models introduced during Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) time created a balanced economic system based on:

- Risk-sharing (mudarabah, musharakah)

- Ethical trade and transparency (murabaha, salam)

- Access to resources without exploitation (ijara, qard hasan)

- Social welfare and community responsibility (waqf, kafalah)

These models were revolutionary in preventing economic injustice, empowering individuals regardless of social status, and promoting collective prosperity.

5. Institutions and Governance in the Time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH)

The establishment of a just and well-regulated economic system during the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) went beyond individual business models. It involved setting up institutions and governance frameworks that ensured fairness, transparency, and social welfare. The Prophet’s leadership combined spiritual guidance with pragmatic economic management, laying foundations that shaped Islamic finance principles for centuries.

5.1 Role of Bait-ul-Mal (Public Treasury)

Bait-ul-Mal was a central public treasury established under the Prophet’s administration in Madinah to manage state funds and resources with utmost integrity and accountability. The term literally means “House of Wealth” and its role encompassed collecting and distributing public revenues.

Sources of Bait-ul-Mal funds included:

- Zakat (Mandatory Almsgiving): A fixed percentage (usually 2.5%) of wealth paid by eligible Muslims, earmarked for welfare and social justice.

- Sadaqah (Voluntary Charity): Additional donations from the community for various causes.

- Fay’ and Ghanima: Spoils of war and other public gains.

- Public taxes and levies: On trade and land where applicable.

Functions of Bait-ul-Mal:

- Welfare and Social Support: The treasury distributed wealth to the poor, widows, orphans, travelers, and those in debt. This ensured economic inclusion and prevented destitution.

- Public Projects: Funds supported infrastructure such as wells, roads, and marketplaces.

- Financial Stability: Managed wealth redistribution to maintain social balance and reduce inequality.

- Accountability: The Prophet appointed trustworthy officials to oversee the treasury, emphasizing transparency and prevention of misuse.

Impact:

- The Bait-ul-Mal was a pioneering example of a state-managed fund dedicated to economic justice and welfare.

- It prevented hoarding and ensured wealth circulation.

- The treasury supported entrepreneurship by providing financial aid to those in need.

- Modern Islamic finance models, such as zakat management and social funds, are inspired by the principles of Bait-ul-Mal.

5.2 Regulation of Markets in Madinah

Market regulation was crucial to protect consumers, merchants, and the overall economy from fraud, exploitation, and monopolistic practices. The Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) implemented practical policies and appointed supervisors to oversee market activities.

Key regulatory measures included:

- Market Supervision: Officials called muhtasibs monitored markets to ensure fair trade, honest weights and measures, and prohibition of cheating.

- Fair Pricing: Artificial inflation or price manipulation was forbidden. Traders were encouraged to sell at just prices.

- Prohibition of Fraud: Deceptive practices, hidden defects, or misrepresentations in products were punishable offenses.

- Preventing Hoarding and Monopoly: Traders who deliberately withheld goods to raise prices faced reprimands or penalties.

- Open Market Days: The Prophet encouraged open and accessible marketplaces, reducing barriers to trade.

From Hadith:

- The Prophet said,

“Give the worker his wages before his sweat dries.” (Sunan Ibn Majah)

emphasizing timely and fair payment. - He also said,

“Whoever cheats is not one of us.” (Sahih Muslim)

highlighting the moral imperative of honesty.

Impact:

- Ensured consumer protection and confidence in trade.

- Enhanced market efficiency by minimizing disputes and fraud.

- Maintained price stability, which supported both merchants and consumers.

- Fostered a culture of ethical business, rooted in trust and social responsibility.

5.3 Role of the Prophet as a Regulator and Businessman

Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) was not only a spiritual leader but also a pragmatic regulator and entrepreneur who exemplified the highest standards of business ethics and governance.

As a Businessman:

- Before prophethood, he was known for his integrity, earning the nickname Al-Amin (The Trustworthy).

- He managed trade caravans for Khadijah (RA), practicing fairness, transparency, and reliability.

- His business dealings avoided interest, deception, and exploitation, setting a practical model for Islamic commerce.

As a Regulator:

- He enforced Shariah principles in economic transactions.

- He personally adjudicated trade disputes, often emphasizing reconciliation and fairness.

- He encouraged contractual clarity, proper documentation, and mutual consent.

- The Prophet implemented policies that balanced individual rights with community welfare.

Example of Leadership:

- When confronted with market manipulation, the Prophet intervened directly to reprimand those responsible and restore justice.

- He ensured that market officials acted impartially and upheld the ethical standards prescribed by Islam.

Impact:

- His leadership established trust in the economic system, encouraging active participation in trade and investment.

- By combining spiritual values with practical governance, he created an environment where business thrived without compromising ethics.

- His example remains a cornerstone for contemporary Islamic finance leaders and regulators.

The institutional and governance framework during Prophet Muhammad’s (PBUH) time was innovative and comprehensive. The Bait-ul-Mal ensured equitable wealth distribution and social support; market regulation protected all stakeholders, fostering trust and efficiency; and the Prophet’s personal role as regulator and businessman set an ethical standard inspiring all economic actors. Together, these elements formed a resilient and just economic ecosystem aligned with Islamic values.

6. Women and Finance in Early Islam

Women’s participation in economic activities during the early Islamic period was both significant and well-supported by Islamic teachings. Contrary to some misconceptions, women in the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) enjoyed financial independence, ownership rights, and the ability to conduct business — all protected and encouraged by Islamic law.

6.1 Khadijah (RA) and Her Business Model

Khadijah bint Khuwaylid (RA), the first wife of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), is one of the most prominent examples of a successful businesswoman in Islamic history. She was a wealthy and respected merchant in Mecca long before her marriage.

- Wealth and Status: Khadijah inherited and expanded her family’s trading business, which involved long-distance caravans trading in spices, textiles, and other goods between Arabia, Syria, and Yemen.

- Entrepreneurship and Management: She was actively involved in managing trade operations, investment, and partnership decisions.

- Employment of the Prophet (PBUH): She employed Muhammad (PBUH) as her chief agent to manage caravans, impressed by his honesty and efficiency.

- Independent Wealth: Khadijah’s financial independence was well-known; she owned property, engaged in contracts, and made decisions without male oversight.

Impact of Khadijah’s Her Business Model

- Role Model: Khadijah’s success demonstrated women’s capability in finance and business within Islamic society.

- Supportive Marriage: Her financial resources supported the Prophet’s mission, showing that economic power could coexist with spiritual leadership.

- Encouragement of Women’s Economic Participation: Khadijah’s example helped establish that women could be economically active contributors in society.

6.2 Women’s Rights in Ownership and Trade

Islamic teachings explicitly affirm women’s rights to own property, manage wealth, and engage in trade independently of male guardians. These rights were revolutionary in the 7th-century Arabian context.

Key Aspects:

- Ownership Rights: Women could inherit property, receive gifts, and hold assets in their own name. The Quran outlines specific shares for women in inheritance (Quran 4:7).

- Business Contracts: Women had full legal capacity to enter contracts, buy and sell goods, and employ workers.

- Trade and Commerce: Many women engaged in market activities, such as selling food, textiles, or handicrafts, and were respected traders.

- Financial Independence: Women’s wealth remained their own property, not automatically controlled by husbands or male relatives.

- Legal Protection: Islamic courts respected women’s financial rights and upheld contracts they entered into.

From Early Islamic History:

- Aisha (RA), the Prophet’s wife, was known to own and trade goods.

- Nusaybah bint Ka’ab (Umm Ammarah), was a trader and warrior, illustrating the active social role of women.

- Female companions were often involved in charitable endowments (waqf), directly influencing community welfare.

Social and Economic Impact

- Empowerment and Inclusion: Women’s financial autonomy promoted their social empowerment and reduced dependency.

- Economic Growth: Women’s participation expanded market activity and diversified economic sectors.

- Fairness and Justice: By guaranteeing women’s property rights, Islam contributed to a more equitable society.

- Legacy for Modern Islamic Finance: Contemporary Islamic finance continues to emphasize women’s economic roles, encouraging their entrepreneurship and financial inclusion in line with early Islamic precedents.

Women in early Islam, epitomized by Khadijah (RA), enjoyed substantial financial rights and actively participated in trade and business. Islamic principles ensured their ownership rights and economic freedom, setting a foundation for gender equity in finance. These early practices not only empowered women socially and economically but also enriched the entire Muslim community.

Comparative Analysis with Modern Islamic Finance

Islamic finance today stands as a sophisticated, global system rooted deeply in the ethical and economic principles introduced during the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). Modern Islamic banking and financial products reflect, adapt, and expand upon the foundational models and governance established over 1400 years ago, while responding to contemporary financial complexities and regulatory environments.

7.1 Legacy of Early Models in Today’s Islamic Banking

Many foundational Islamic finance contracts and concepts trace their origins directly to the business and economic practices of the Prophet’s era. Key principles such as risk-sharing, prohibition of interest (riba), asset-backed transactions, and ethical trading have been preserved and institutionalized.

Early Models Today:

- Mudarabah and Musharakah: These profit-and-loss sharing contracts form the backbone of many Islamic investment products and partnership arrangements used in modern Islamic banks.

- Murabaha (cost-plus financing): Widely used for asset financing and home loans, it is based on the principle of transparent markup rather than interest.

- Ijarah (leasing): Commonly used for vehicle and equipment leasing, echoing the Prophet’s leasing contracts.

- Qard Hasan: Interest-free loans continue to be offered by Islamic banks for social welfare or emergency financing.

This legacy ensures that Islamic finance is not merely about avoiding interest but embraces comprehensive ethical finance rooted in social justice and economic equity.

Read More: Eid-Ul-Adha: A Holy Tradition and Its Socioeconomic Dimensions

7.2 Shariah Boards: Guardians of Compliance

Unlike the Prophet’s personal role as regulator, modern Islamic finance institutions rely on Shariah boards—panels of Islamic scholars and experts—to oversee financial products and practices.

Functions of Shariah Boards:

- Ensure Compliance: They review and certify that banking products conform to Islamic law.

- Interpretation: Adapt classical jurisprudence to modern economic realities, ensuring relevance and legitimacy.

- Advisory Role: Guide banks on ethical and religious issues.

Comparison:

- The Prophet himself was the singular authority and ethical exemplar.

- Today’s Shariah boards represent collective expertise, necessary due to the complexity of modern finance and global regulatory environments.

Shariah boards maintain continuity with early Islamic principles while addressing new challenges like derivatives, international finance, and digital banking.

7.3 Takaful (Islamic Insurance)

Takaful is a modern innovation rooted in the concept of mutual assistance and risk-sharing, principles aligned with the communal solidarity emphasized in early Islamic society.

- Early Islam forbade conventional insurance because of gharar (excessive uncertainty) and riba.

- Takaful provides cooperative risk-sharing among participants, reflecting the ethos of social welfare seen in waqf and qard hasan.

Similarity:Both systems aim to distribute risk fairly and prevent exploitation.

Difference: Early Islam had no formal insurance system; takaful developed to meet modern needs, with contractual mechanisms ensuring compliance with Shariah.

7.4 Sukuk (Islamic Bonds)

Sukuk are modern financial certificates representing ownership in tangible assets, usufructs, or services, designed to comply with Islamic prohibition of interest-bearing bonds.

- Early Islamic finance emphasized asset-backed transactions and profit-loss sharing.

- Sukuk embody this principle by linking returns to asset performance rather than fixed interest.

Similarity: Both Sukuk and early contracts such as mudarabah and musharakah involve risk-sharing and asset linkage.

Difference: Sukuk are structured financial instruments that enable large-scale fundraising on global capital markets, which was not possible in the early Islamic period.

7.5 Differences and Similarities Between Early and Modern Islamic Finance

| Aspect | Early Islamic Finance | Modern Islamic Finance |

| Authority | Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) as sole regulator | Shariah boards and scholars as regulators |

| Scope of Transactions | Trade, partnerships, leasing, lending | Wide array of banking, capital markets, insurance |

| Contract Complexity | Simple, direct contracts | Complex structures adapted for modern economy |

| Risk Sharing | Central concept | Core principle preserved and expanded |

| Interest (Riba) | Strictly prohibited | Prohibited; modern substitutes developed |

| Market Regulation | Prophet-led supervision | Regulatory bodies and legal frameworks |

| Social Welfare | Bait-ul-Mal and waqf as social funds | Zakat funds, charity accounts, microfinance |

Continuity: The ethical foundation, prohibition of injustice, emphasis on fairness, and social justice remain central.

Evolution: The system has evolved to accommodate complex financial needs, regulatory environments, and global markets while adhering to core Islamic values.

Modern Islamic finance is a dynamic continuation and expansion of the economic principles established in the time of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH). It balances religious mandates with financial innovation to serve the needs of Muslim and non-Muslim communities worldwide. Through Shariah boards, takaful, sukuk, and other instruments, the legacy of early Islamic economic models persists, ensuring finance serves humanity ethically, transparently, and equitably.

8. Challenges and Evolution of Islamic Finance

8.1 Decline of Islamic Finance Post-Khilafah Era

After the era of the Prophet Muhammad (PBUH) and the Rightly Guided Caliphs, Islamic finance began to face significant challenges, particularly as Islamic empires expanded and encountered diverse administrative, cultural, and economic systems. Over time, several factors contributed to the weakening of the Islamic financial model:

- Colonial Influence: During the colonial period (18th–20th centuries), European powers imposed Western-style banking and legal systems in Muslim-majority regions. Interest-based financial institutions gradually replaced Islamic ones, and traditional Islamic courts lost authority.

- Erosion of Islamic Institutions: Institutions like Bait-ul-Mal and waqf (charitable endowments) lost autonomy or were abolished, reducing community-driven financial management.

- Decline of Ijtihad (independent reasoning): Islamic jurisprudence stagnated in many areas, including finance. Without active scholarly engagement, Islamic economic principles failed to evolve alongside changing markets and technologies.

- Disconnection from Trade: Islamic societies, once global hubs of commerce, fell behind economically and technologically during periods of internal strife and colonization.

As a result, Islamic financial practices became limited to personal transactions and informal community dealings, while large-scale economies operated under conventional (interest-based) models.

8.2 Islamic finance in the 20th and 21st Centuries

The mid-20th century marked the revival of Islamic finance as scholars and economists sought to reconnect Islamic principles with modern financial tools.

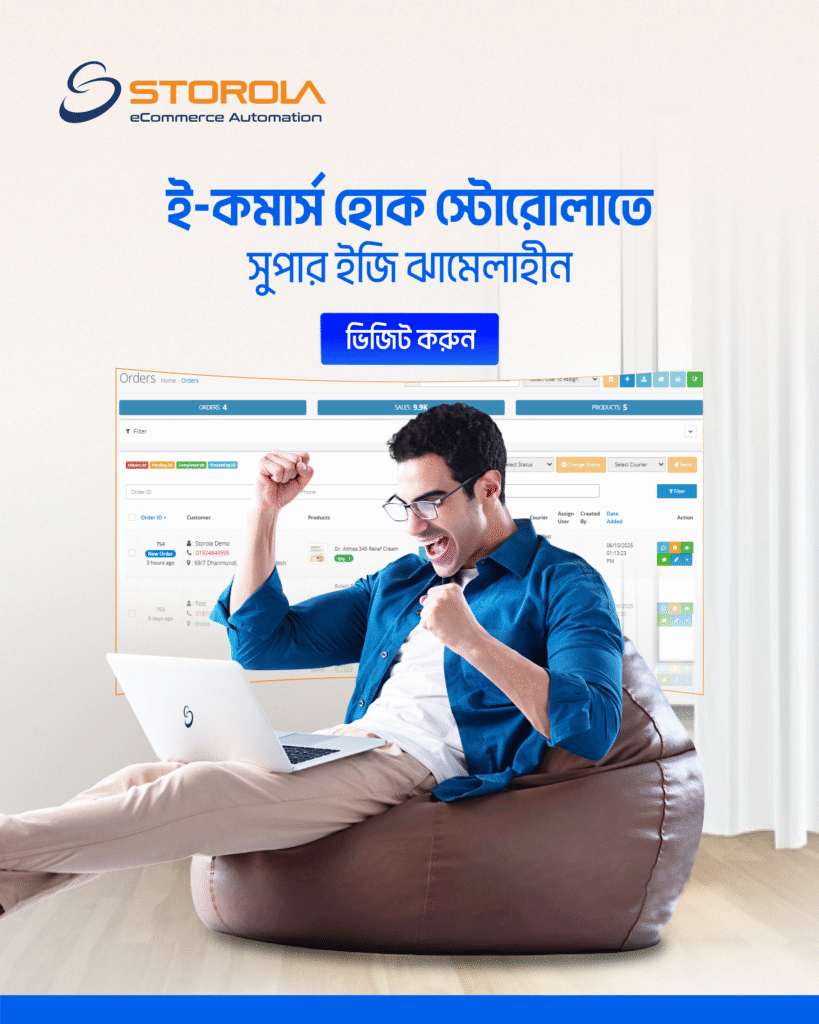

| Period | Milestone/Event | Impact |

| 1963 | Mit Ghamr Savings Bank (Egypt) | First modern Islamic bank using profit-sharing, not interest. Proof-of-concept for Islamic finance. |

| 1975 | Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and Dubai Islamic Bank established | Institutional foundation for international Islamic banking. |

| 1980s–1990s | Islamic banks spread across Middle East, South Asia, Southeast Asia | Rise of Shariah-compliant banking systems. Iran, Pakistan, Sudan began full Islamization. |

| 2000s–2010s | Growth in regulations, products (sukuk, takaful), and cross-border finance | Integration with global finance systems. |

| 2010s–Present | Expansion into non-Muslim-majority countries like UK, Hong Kong, South Africa | Mainstream recognition of Islamic finance principles; sukuk traded in international markets. |

- 1963: Establishment of Mit Ghamr Savings Bank in Egypt—the first modern interest-free bank.

- 1975: Founding of the Islamic Development Bank (IDB) and Dubai Islamic Bank, paving the way for global Islamic banking.

- 1980s–1990s: Spread of Islamic financial institutions across the Middle East, Southeast Asia, and South Asia. Governments in countries like Iran, Pakistan, and Sudan attempted full Islamization of their banking sectors.

- 2000s–Present: Widespread adoption of Islamic finance in global markets, including the UK, Malaysia, UAE, Indonesia, and even non-Muslim-majority countries.

Modern Features:

- Shariah-compliant products: Musharakah, Murabaha, Ijarah, and Sukuk became mainstream financial instruments.

- Takaful and Islamic microfinance: Broadened the reach of Islamic finance to insurance and poverty alleviation.

- Global regulation and standardization: Institutions like AAOIFI (Accounting and Auditing Organization for Islamic Financial Institutions) and IFSB (Islamic Financial Services Board) provide standards for global consistency.

Challenges Still Faced:

- Standardization Issues: Differences in interpretation among schools of thought sometimes create inconsistencies in product design.

- Integration with global finance: Navigating dual compliance with Shariah and secular financial laws remains complex.

- Ethical Concerns: Some critics argue that modern Islamic finance focuses more on technical compliance than on the spirit of Islamic ethics, such as fairness, risk-sharing, and social justice.

Despite these challenges, Islamic finance has shown remarkable resilience and adaptability, growing into a trillion-dollar industry serving diverse populations.

Conclusion

The foundations of Islamic finance, as established during the lifetime of Prophet Muhammad (PBUH), represent a profound integration of ethical, social, and economic values. Far beyond mere prohibitions, this system emphasized justice, transparency, mutual consent, and the fair distribution of wealth. From the early trade practices in Makkah to the market regulation in Madinah, the Prophet shaped a financial model rooted in fairness and guided by divine principles. Women, too, held prominent roles, as exemplified by Khadijah (RA), the Prophet’s wife and a successful businesswoman, illustrating Islam’s early commitment to women’s economic rights.

Although the Islamic financial model declined after the fall of the Khilafah and the rise of colonial systems, its resurgence in the 20th and 21st centuries proves the lasting relevance of those early principles. Today, modern Islamic finance—through instruments like sukuk, takaful, and Islamic banking—has grown into a global industry serving millions of people across diverse cultures. Institutions such as Shariah boards, Islamic microfinance organizations, and fintech platforms are working to adapt these ancient principles to modern-day challenges. While modern structures may differ in form and complexity, the spirit of ethical finance, rooted in mutual benefit, remains central.

References: