Have you ever purchased a cup of tea from a footpath stores? Or taken a ride in battery-powered Auto rickshaws to navigate the city’s rush? These simple everyday conveniences are often powered by individuals whose lives remain invisible to most of us.

people whose sweat keeps our lives running, whose homes are lit by serving our daily needs. And yet, through constant eviction drives, they’re losing not just their livelihoods but their dignity

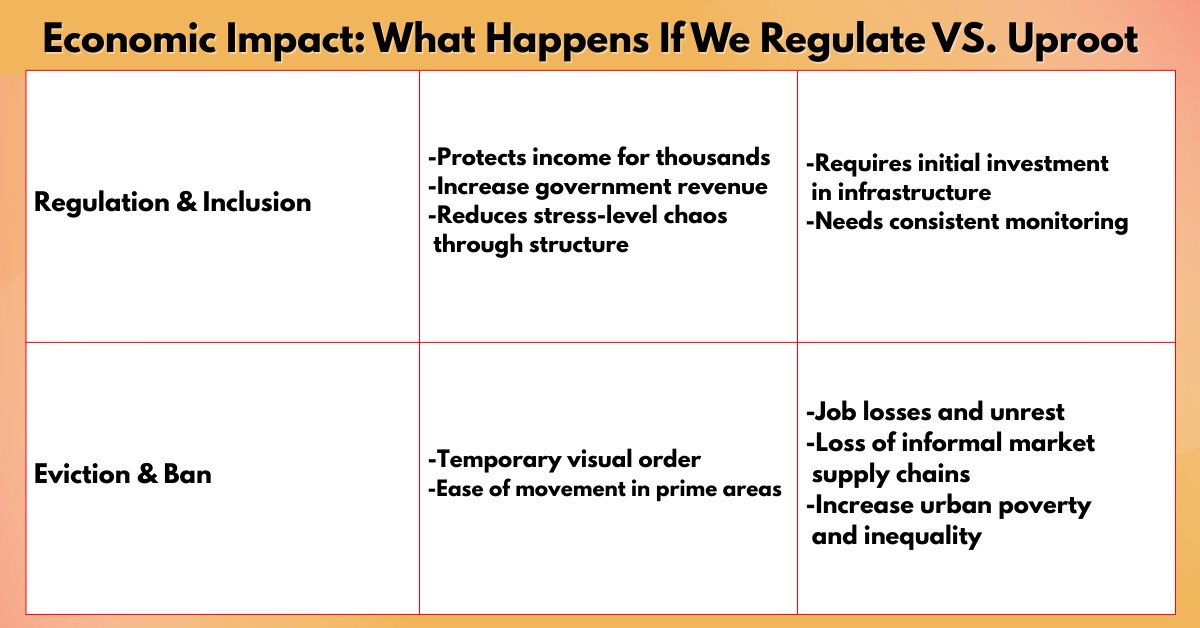

In recent times, we’ve seen increasing initiatives to remove battery-powered auto rickshaws and Footpath stores from urban areas in the name of better traffic management and city beautification. While the intentions may be valid, we must also ask that what are the broader social and economic implications of such actions? we also need to think about how this affects people’s lives. Instead of just removing them, we should look for fair and kind solutions ones that keep the city in order but also protect people’s livelihoods.

Introduction

Bangladesh stands at a dynamic crossroads of rapid urbanization and deep-rooted tradition. As city skylines rise and traffic flows intensify, two familiar elements of the streets-cape is footpath stores and battery-powered auto rickshaws have emerged not just as urban fixtures, but as vital lifelines for millions of people. They represent much more than convenience or congestion; they are the heartbeat of the informal economy, the refuge of the working class, and a reflection of how resilience, necessity, and innovation shape everyday life in a developing nation.

Yet, these symbols of survival are now at the center of contentious policy debates. From eviction drives to regulation crackdowns, the future of footpath Stores and auto rickshaw drivers hangs in a delicate balance between urban order and economic justice. This article explores the complex interplay between these grassroots livelihoods and the challenges of modern city governance, revealing not only the tensions but also the immense opportunities that lie in thoughtful, inclusive urban policy.

Footpath Stores in Bangladesh

In Bangladesh, footpath stores are not just informal stalls, they are a way of life. They serve as low-cost entry points for thousands of families. Particularly from the lower-middle and working classes, to engage in commerce. From clothing to snacks, mobile accessories to fresh fruits, these stalls provide daily essentials to millions, while simultaneously offering livelihood to the vendors.

-

Most operate informally—without formal registration or trade licenses.

-

Agreements with local authorities are often verbal or unofficial.

-

However, these setups obstruct pedestrian movement and detract from urban aesthetics, leading to calls for eviction.

More than 5 million people in Bangladesh are directly or indirectly dependent on footpath-based retail. These micro-enterprises thrive due to three main factors:

-

Low setup costs

-

High foot traffic

-

Lack of formal employment opportunities

However, these stalls often face eviction drives due to urban development goals. Authorities cite reasons such as:

-

Blocking pedestrian movement

-

Causing traffic congestion

-

Violating city planning laws

But eviction without alternatives often leads to social unrest, income loss, and increased urban poverty.

Market Potential:

-

Bangladesh has over 5 million street vendors (Informal Economy Report 2022).

-

Formalizing and regulating this sector could result in annual transactions exceeding BDT 2,000 crore (approx. USD 182 million).

-

Cities can introduce vendor ID cards, digital mapping, and vendor time shifts to manage congestion.

Why Alternatives Are Needed

While regulation is necessary for maintaining public order, humane alternatives must be considered to balance the rights of both pedestrians and informal workers. Alternatives help ensure their lives. Including:

-

Livelihood protection

-

Urban space efficiency

-

Improved public safety and order

Local Innovations in Managing Footpath Stores: The Bangladesh Experience

While cities like Ahmedabad and Delhi in India have made remarkable progress in structuring street vending through acts like the street vendors Act, 2014, Bangladesh too has initiated meaningful efforts to balance urban order with the economic needs of footpath stores. From Mirpur to Mohammadpur, several initiatives reflect how our urban spaces can evolve into inclusive environments without sacrificing livelihood or public convenience.

In Mirpur and Uttara, the Dhaka North City Corporation (DNCC) has piloted a street vendor registration program, revealing that over 90% of stores are willing to cooperate with formal systems. The initiative aims to bring discipline to street vending through proper registration, licensing, and offering protection from eviction or exploitation. Instead of random eviction drives, this approach respects the economic realities of vendors while helping the city maintain order.

Another example comes from BRAC’s Urban Development Programme (UDP), active in Mirpur and Mohammadpur, where efforts have gone beyond basic income support. BRAC has supported urban footpath stores with access to health care, sanitation supplies and COVID-19 vaccinations through its community health centers. These actions not only improve vendors quality of life but also contribute to building healthier urban ecosystems.

Certain areas in Dhaka, such as Khilgaon Pallima Sangsad and Mohammadpur Town Hall, have naturally developed into semi-structured food vending zones. These hubs serve thousands of customers daily with affordable meals and snacks, proving that organized vending can serve both economic and public interests without formal eviction. Though not officially designated, their success hints at the potential of transforming other areas into recognized vending zones.

One of the most vibrant examples is Love Road in Mirpur, now a beloved weekend destination for youth and food lovers. It has organically grown into a bustling street food hub, offering everything from fuchka to fried chicken, and demonstrating how structured chaos can sometimes serve as a blueprint for inclusive urban planning.

These examples show that instead of enforcing blanket evictions or restricting mobility, city corporations and local stakeholders can create designated vending zones, possibly through licensing and public-private partnerships. Parks, unused government land, bus terminals, or even school grounds after school hours can be repurposed for such vending zones.

By learning from both international models and our own local successes, Bangladesh can pave the way for an urban economy that is inclusive, sustainable and helpful for everyone.

Establishing Alternative Solutions Through Designated Spaces

Eviction alone is not the solution. What we need are sustainable and alternatives. One effective solution could be to designate specific areas where footpath vendors are allowed to operate. For example:

-

Park gate areas in the city

-

Vacant government-owned lands

-

Designated zones near bus terminals

-

Weekly market grounds

-

Even school or college premises during off-hours.

These spaces could be allocated under certain conditions or for specific times. City corporations or municipalities could implement a tender or licensing system to formally allow vendors to operate in these designated areas. This would ensure:

-

Unobstructed pedestrian movement

-

Preservation of urban aesthetics

-

And continued livelihood opportunities for the vendors.

This approach would not only help maintain order in urban areas but also protect the income sources of underprivileged communities.

Economic Potential of Footpath Stores (If Formalized)

If formalized with proper licensing and oversight, footpath stores in Bangladesh could contribute:

-

Over ৳2000 crore annually to the informal economy

-

Create safer, organized, and more accessible urban retail experiences

-

Provide job security to millions of low-income earners

Challenges to Address

Despite these alternatives, several barriers remain:

-

Lack of political will and coordination among city corporations

-

Resistance from private businesses fearing unfair competition

-

Public perception of footpath vendors as illegal squatters

Rather than eviction, integration and regulation should be the strategy. City authorities must recognize footpath stores as part of the urban economy, not an obstacle to it. By embracing smart, inclusive planning, Bangladesh can not only preserve livelihoods but also create cleaner, more efficient cities.

The Rise of Auto Rickshaws in Bangladesh- A Rising Force in Urban Mobility

In recent years, Bangladesh has witnessed an explosive growth in the number of auto rickshaws. Not just in Dhaka, but across urban and semi-urban areas, these battery-powered three-wheelers have transformed how people move.

In the bustling urban landscape of Dhaka the rapid increase in battery-operated rickshaws popularly referred to as “Banglar Teslas” has significantly transformed the city’s transportation system, while simultaneously raising important concerns about safety and regulatory oversight. With nearly 4 million such vehicles now operating across the country, their rise reveals both a transportation solution and a new urban challenge.

Why Auto Rickshaws Took Over the Streets

At the core of this boom lies a fundamental issue in Bangladesh’s transportation infrastructure a severe shortage of public transport. Only 2% of registered vehicles in the country are buses or minibuses. This creates a massive gap in mass mobility services one that auto rickshaws have rushed to fill.

Auto rickshaws offer affordable, accessible, and fast transport compared to traditional paddle rickshaws or costly ride-share options. As inflation pushes up fares for all forms of travel, many people are turning to these battery-operated vehicles as a more economical alternative.

This trend reflects a well-known economic principle the substitution effect, where consumers shift to lower-cost alternatives when prices rise. In this case, battery-powered rickshaws have emerged as the substitute for both inefficient public buses and physically demanding paddle rickshaws.

From Tradition to Transition: Why Drivers Are Switching to Auto Rickshaw

Paddle rickshaws, once a dominant mode of transport and income for thousands, are now being left behind. Many traditional rickshaw pullers are either retrofitting their vehicles with batteries or abandoning them altogether for auto rickshaws.

The reason? Better income, lower effort, and quicker returns.

Ali Hossain, a veteran rickshaw manufacturer with four decades of experience, said that “I’ve stopped making paddle rickshaws. There’s no demand anymore. People want to reach their destinations quickly auto rickshaws serve that need.”

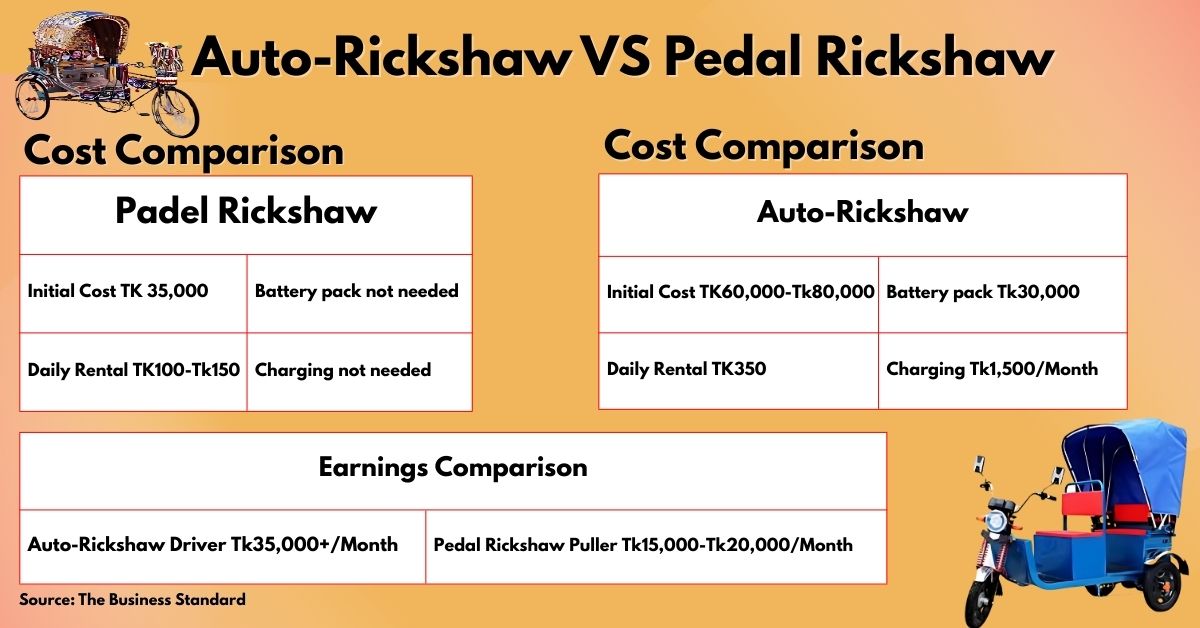

Building a standard paddle rickshaw costs about BDT 35,000 or less, while a new battery-powered one costs between BDT 60,000 to 80,000. Despite the higher upfront investment, the returns are quicker. An auto rickshaw typically includes four 12-volt batteries, a motor, lights, and other basic electronics. Batteries cost around BDT 30,000, with a lifespan of 6 months to 1 year. However, when returned after six months, they fetch nearly half their value back.

Md. Wahid Islam, a 52-year-old auto rickshaw driver in Shahbagh, says that

“We give around BDT 350 per day to the owner. Charging costs about BDT 50 daily, totaling around BDT 1,500 a month. Still, we can make over BDT 35,000 a month.”

In contrast, paddle rickshaw drivers earn between BDT 15,000–20,000 per month, often at the cost of their physical health. Many struggle with fatigue, illness, and a lack of sustainable income.

The appeal of auto rickshaws isn’t just about comfort, it’s about survival.

The Economics Behind the Wheels

The growth of battery rickshaws isn’t accidental it’s driven by economic incentives at every level. From garage owners to battery sellers, a whole ecosystem thrives on the rising popularity of these vehicles. According to Professor Dr. Md. Shamsul Haque, Director of the Accident Research Institute (ARI) at BUET:

“In economics, maximizing profit is the goal. Auto rickshaws generate more income, so garage owners and investors naturally encourage this model.”

Indeed, the low cost of operation and high passenger turnover makes these vehicles an attractive investment. However, like any fast-growing, loosely regulated industry, auto rickshaws come with serious consequences specially for road safety and urban infrastructure.

The Safety Crisis

The most alarming downside to the rise of auto rickshaws is their impact on road safety. These vehicles often lack proper engineering standards. Built locally, many are retrofitted without any safety protocols. Unlicensed and untrained drivers further exacerbate the problem.

Recent tragedies underscore the risk. Afshana Karim, a student at Jahangirnagar University, lost her life in a tragic auto rickshaw accident on campus one of many such incidents that occur across the country. From January to October, there were nearly 900 accidents involving battery-powered rickshaws. Over 582 of these were classified as serious.

Professor Haque warns that “Small vehicles are becoming a leading cause of road accidents. If road infrastructure isn’t properly planned and executed, accidents are inevitable.”(Reference: TBS)

He emphasizes the importance of a tiered transport strategy:

- Pedestrians first – wide, usable footpaths

-

Mass transit second – efficient public transport

-

Auto rickshaws last – designated lanes and stricter regulation

Without this structure, urban mobility will become increasingly chaotic and dangerous.

Powering the Problem: Environmental and Infrastructure Strain

Auto rickshaws may reduce individual travel costs, but they place significant strain on national infrastructure. Each vehicle requires 7 to 8 hours of charging using 48–60 ampere chargers. Multiply that by millions, and the pressure on Bangladesh’s power grid becomes evident specially in areas already facing frequent load shedding.

There’s also an environmental threat. Batteries are often discarded improperly, releasing toxic chemicals into soil and water. With no standardized battery recycling program in place, this could snowball into a major environmental crisis.

In Professor Haque’s words is that “When floodwaters rise, we close the floodgates first. Similarly, to control the auto rickshaw surge, we must begin by restricting imports of auto rickshaws and batteries.”

Toward a Smarter Urban Future

Auto rickshaws have become an indispensable part of urban life in Bangladesh. They provide employment to hundreds of thousands and offer affordable transport for millions. But unregulated expansion risks turning a solution into a crisis. The challenge now lies in balancing innovation with infrastructure, access with accountability, and mobility with safety.

It’s time for policy-makers to step in not to eliminate auto rickshaws but to regulate, organize, and innovate. Dedicated lanes, licensing systems, mandatory safety inspections, battery recycling programs, and integration into broader transport planning are no longer optional they are essential. Because the future of urban transport in Bangladesh must be efficient, inclusive, and safe not just fast and cheap.

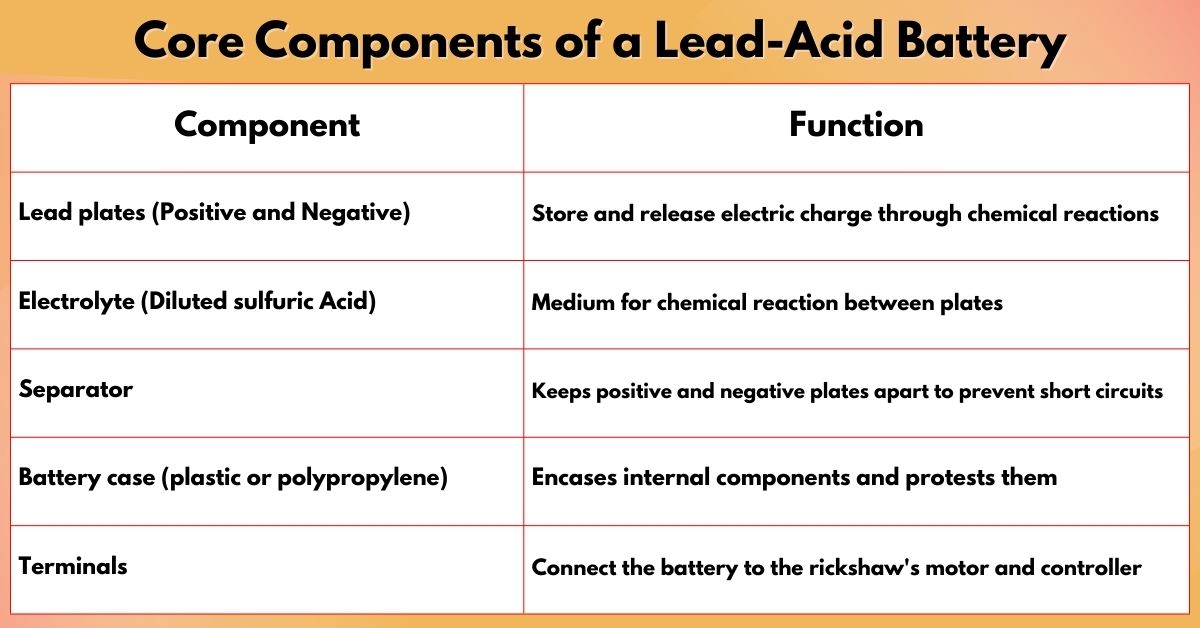

Structure of Auto Rickshaw Batteries

Battery-powered auto rickshaws in Bangladesh mostly use lead-acid batteries though some newer or higher-end models may use lithium-ion batteries. Here’s how their structure and components look:

Battery Type

-

Most common: Sealed lead-acid (SLA) or Flooded lead-acid batteries

-

Emerging type: Lithium-ion (Li-ion) batteries in high-end models

Number of Batteries

-

Typically, one auto rickshaw uses 4 batteries

-

Each battery is 12 volts (V), combining to supply a 48V system

Battery Capacity

-

Ampere-hour (Ah) rating: Between 100Ah and 130Ah

-

This determines how long the battery can provide power

-

Higher Ah = longer range but higher weight and cost

Battery Charger

-

Voltage: 48V charger required

-

Current Output: 8A to 15A depending on charging time and battery size

-

Takes about 7–8 hours for a full charge

-

Plugged into household or garage power supply

Battery Life

-

6 to 12 months, depending on:

-

Quality of battery

-

Charging habits

-

Road and weight conditions

-

-

After 6 months, batteries often lose efficiency

-

Some shops offer partial buy-back or replacement value on old batteries

Cost of Battery Set

-

Total cost for 4 lead-acid batteries: BDT 28,000 to 35,000

-

Lithium-ion sets can cost BDT 60,000+, but they last longer and charge faster

Environmental Concern

-

Used batteries are often dumped improperly, causing soil and water contamination

-

Batteries contain lead, acid, and heavy metals—hazardous to human health and ecosystems

-

Proper recycling systems are still missing in most areas

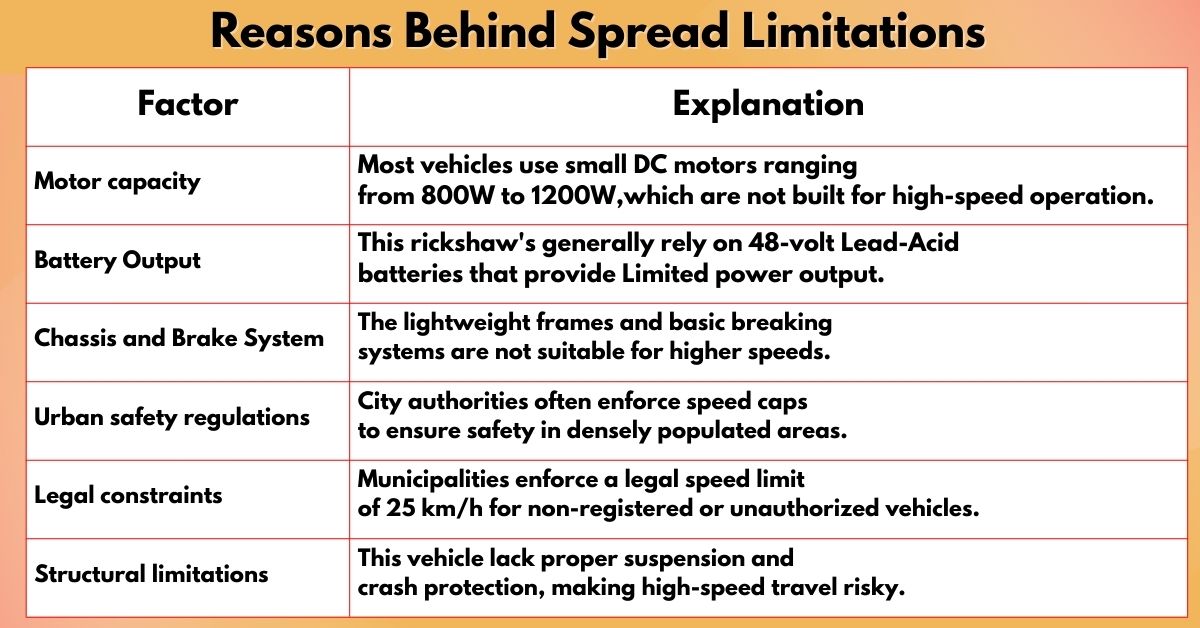

Designed Speed Range

Battery-powered auto rickshaws in Bangladesh are typically limited to a maximum speed of 25 to 35 kilometers per hour. In some cases, factory-assembled or higher-end models may reach speeds of 40 to 45 kilometers per hour, though these are not widespread due to cost and regulation.

Speed Degradation Over Time

As batteries degrade, the power they supply diminishes. This leads to a decrease in maximum speed, which can drop to 15–20 km/h in older vehicles. Additional factors like worn-out motors and extra passenger weight further slow the vehicle.

Implications of Low Speed

-

Suitable for short-distance, intra-city travel.

-

Inadequate for long-distance or highway use.

-

Can create traffic congestion when mixed with faster-moving vehicles.

-

Low speeds help reduce accident severity but also highlight the need for clear regulation and designated lanes.

Alternatives to Auto Rickshaws: Toward Safer and Smarter Urban Mobility

Battery-powered auto rickshaws in Bangladesh

has created new challenges in traffic management, safety, and environmental sustainability. Simply banning or removing them, however, is not the answer. Instead, urban planners and policymakers must develop practical, inclusive alternatives that offer safe, affordable, and environmentally responsible transportation, while protecting the livelihoods of thousands of drivers.

Read More: Youth Self Employment Empowered with Tk100 Crore Budget Fund Plan

Here are several feasible alternatives to consider:

1. Improved Public Transport Systems

A key reason for the rise of auto rickshaws is the lack of dependable and widespread public transportation.

Solutions:

-

Expand Bus Rapid Transit (BRT) systems in major cities to cover high-demand routes.

-

Introduce smaller feeder buses to navigate narrow lanes in urban neighborhoods.

-

Ensure affordable, frequent, and timely services specially during peak hours.

-

Offer student, elderly, and low-income commuter discounts to make mass transport more accessible than auto rickshaws.

Benefits:

-

Reduces traffic congestion

-

Enhances safety and regulation

-

Lowers per-capita carbon emissions

2. E-Bus and E-Mini Van Services

Bangladesh can look toward electric mini-buses and vans as low-emission alternatives to battery-powered rickshaws.

Examples:

-

3-wheeler e-vans for short distances, particularly in residential and school areas

-

Electric shuttle services in densely populated commercial zones

Benefits:

-

Eco-friendly

-

Longer battery life than auto rickshaws

-

Safer with better seating and enclosure

-

Easier to regulate under a formal transit authority

3. Non-Motorized Transport (NMT) Lanes

Reintroducing and protecting traditional paddle rickshaws and promoting bicycles can serve as a greener and safer solution in select areas.

Strategies:

- Create dedicated NMT lanes for rickshaws and cycles

- Provide incentives for traditional rickshaw drivers to operate in designated zones like school perimeters or market areas

- Launch bike-sharing programs in Dhaka and Chattogram

Benefits:

- Zero emissions

- Safe speed limits

- Preserves cultural identity

- Promotes physical health

4. Ride-Sharing and Micro-Transit Integration

Formalizing a network of small, regulated ride-sharing vehicles using smartphone apps and real-time route planning could be a modern-day solution to auto rickshaws.

Ideas:

-

Launch government-supported ride-share services using CNG, e-scooters, or small EVs

-

Allow female-only ride services to improve safety and inclusivity

-

Use GPS tracking, seat belts, insurance, and regulated driver training

Benefits:

-

Real-time availability

-

Safer for passengers

-

Digitally traceable

-

Brings informal transport into the formal digital economy

5.Skill Upgrading & Driver Transition Programs

Thousands of families depend on auto rickshaws for survival. Any change must offer a pathway to transition.

Support can include:

-

Vocational training in vehicle maintenance, electronics, or delivery services

-

Loans or grants to switch to formal transport jobs

-

Partnerships with logistics firms for last-mile delivery hiring

Impact:

-

Reduces dependency on unregulated vehicles

-

Builds long-term employment sustainability

-

Helps diversify driver income sources

6. Eco-Friendly Transportation Startups

Bangladesh’s startup ecosystem can contribute significantly. Encouraging green transport innovation can provide long-term solutions.

Possible ideas:

-

Solar-powered rickshaws

-

App-based tuk-tuk services

-

Rental-based e-bike programs

-

Lightweight electric scooters for short commutes

Support needed:

-

Government grants

-

Startup incubators

-

Public-private innovation challenges

Practical Alternatives to Uprooting Footpath Vendors and Auto Rickshaws

Bangladesh’s growing cities are a mosaic of movement, survival, and ambition. Footpath vendors and battery-powered auto rickshaws have become part of this living system not merely obstacles to urban planning, but active participants in the economy. Rather than taking a hardline approach of eviction or bans, it is time to explore more humane and practical alternatives that balance public order with people’s livelihoods.

1. Designated Vendor Zones

Instead of completely removing footpath vendors, city corporations can set up regulated street markets. Specific locations such as areas outside parks, bus terminals, and even school grounds after hours can be converted into designated vending zones. These markets could operate during specific times of the day, ensuring that public movement is not obstructed.

Benefits:

-

Vendors operate safely without fear of eviction.

-

Citizens enjoy organized, accessible street services.

-

Local governments can issue licenses and collect revenue.

2. Digital Licensing for Battery-Powered Auto Rickshaws

With over 1 million battery-powered three-wheelers running across Bangladesh, these vehicles are not going away. They serve millions with affordable transport—but remain largely informal and unregulated. Instead of blanket bans, it makes more sense to bring them into the formal fold.

Proposed Solutions:

-

A mobile app-based digital registration and licensing system.

-

Zone-specific permits to control traffic congestion.

-

Affordable annual license fee (e.g. BDT 500), which could generate over BDT 50 crore annually in revenue.

This would make the system safer, more transparent and beneficial for both the public and the government.

Realistic Policy Suggestions

-

Create Legal Vendor Zones in Every Ward

Time-regulated, clean, and accessible spaces for footpath vendors to operate legally. -

Digital Licensing for Auto Rickshaws

A cost-effective digital registry that integrates GPS-based permits and driving records. -

Route and Speed Regulation

Specific urban zones for auto rickshaws with speed caps to ensure public safety. -

Microfinance Access for Small Vendors

Small loans and support schemes to help vendors build resilience without falling into debt cycles. -

Collaborative Policy Design

Municipal authorities, NGOs, and representatives of vendors and drivers should co-develop sustainable urban market strategies.

Why This Matters?

Urban spaces are more than concrete and traffic rules. They are lived-in spaces shaped by real people doing their best to survive. A fruit vendor on a footpath, or an auto driver navigating Dhaka’s traffic, is not just part of the economy they’re part of our shared story.

Reforms must consider not only city beautification and traffic decongestion but also economic justice, human dignity, and inclusive growth. These alternatives do not just protect livelihoods they strengthen the very fabric of urban life.

Conclusion: A City for All

Bangladesh is urbanizing rapidly, but real progress lies in inclusive development. Footpath stores and auto rickshaws are not problems to be eradicated they are essential pieces of the urban puzzle. With thoughtful planning, strong policies, and humane governance, these informal sectors can become engines of dignity, innovation, and shared prosperity.

They are a symptom of a broken system. They filled a mobility vacuum left by a lack of investment in public transport. But now, we must go further. The path forward is not about uprooting livelihoods or banning vehicles. It is about evolving together.

We must transition toward smarter, safer, and more sustainable transport not just for the sake of cleaner cities, but to preserve the dignity and income of those who serve our daily commute. By investing in infrastructure, regulation, and innovation, we can build a future where both passengers and drivers feel valued, secure, and hopeful. As we dream of smarter cities, let’s not forget the people who help them run to one cup of tea, one short ride at a time.

Share via: