You might think financial revolutions are born in stock markets or global banks. But one of the biggest financial revolutions in history? That started in the villages of Bangladesh, not in a corporate tower, but under the tin roofs of struggling homes. And the man behind it all? Muhammad Yunus, a quiet professor with a loud idea: “Give the poor money—not as charity, but as credit.” Well, welcome to the world of Microfinance. It’s a special kind of loan system that gives small amounts of money to poor people who want to start a business or improve their lives.

1. Introduction

Imagine a woman in a small village in Bangladesh. She has no land, no job, and no money. But she has a dream to start her own business and give her children a better life. The only thing standing in her way? A lack of money. Just a few hundred taka could change everything. But no bank will trust her. So what can she do? Here, Microfinance helps. Microfinance refers to the provision of financial services, such as microcredit, savings, insurance, and remittance, to low-income individuals or groups traditionally excluded from formal banking. Now they don’t need a rich family, property, or a big education. All they need is an idea and determination.

The primary objective of microfinance is to empower people by enabling them to participate in productive economic activities. Unlike conventional banking, which often relies on collateral, microfinance operates on trust, social collateral, and joint liability.Today, the microfinance industry serves over 200 million people globally, with active players in Asia, Africa, and Latin America. While the majority of beneficiaries are women, its effects extend to households, communities, and economies at large.

2. Historical Background of Microfinance in Bangladesh

The formal introduction of microfinance in Bangladesh began in 1976, when Dr. Muhammad Yunus, a professor of economics at the University of Chittagong, initiated an experimental lending program in Jobra village. He personally provided a loan of $27 (approximately BDT 856 at the time) to 42 impoverished women, enabling them to purchase raw materials for small-scale production. These women had previously relied on exploitative moneylenders, often trapped in cycles of debt. Dr. Yunus’s intervention helped them shift from subsistence to self-reliance, proving that even small credit, when properly structured, could have a transformative impact.

The success of this initial experiment laid the foundation for what would become Grameen Bank, which was formally established in 1983 by a special ordinance of the Government of Bangladesh. What set Grameen Bank apart was its innovative model of group-based lending without physical collateral, its focus on women empowerment, and its emphasis on social development alongside financial inclusion.

Microfinance Effect in Income and Nutrition

- Women in Dhaka: 20% increase in household income.

- Gender-based violence: 30% decrease.

- Women’s involvement in household decisions 45% increase.

- Maternal health: 33% improvement in.

- Child malnutrition rates: 30% decrease.

- Girls’ school attendance rates: 35% rise.

3. Major Microfinance Institutions in Bangladesh

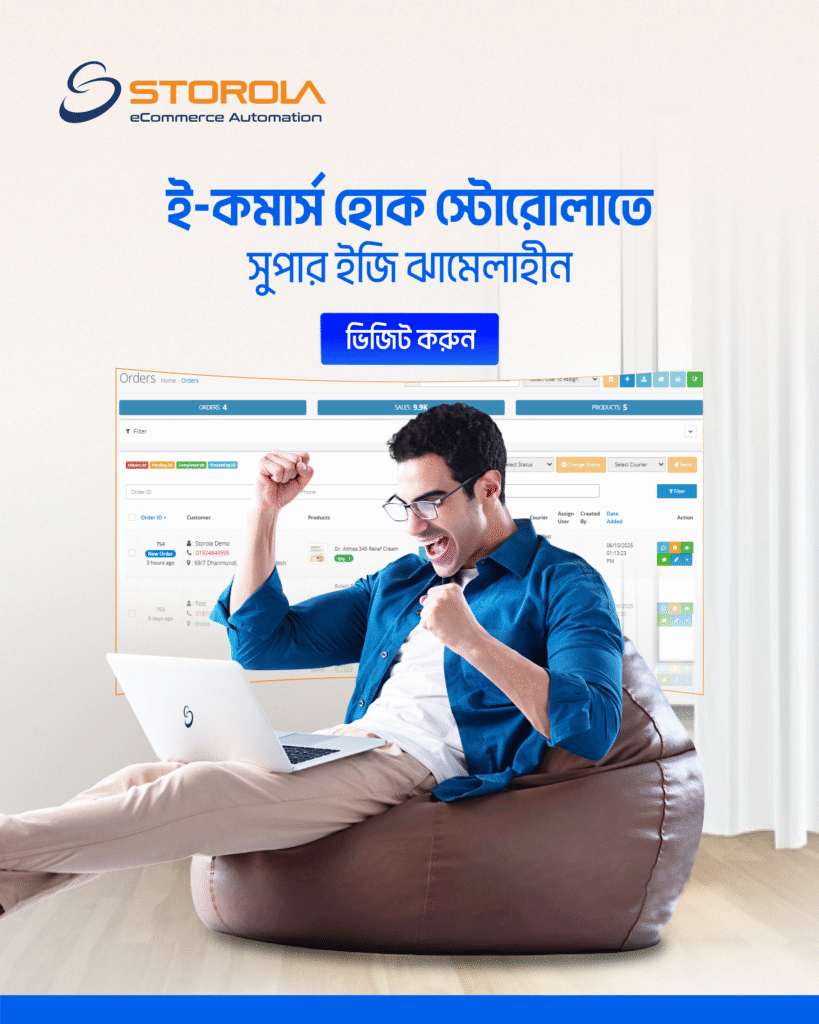

Bangladesh’s microfinance sector has grown into a global model, transforming the lives of millions of low-income households by providing small loans, savings programs, and integrated social services. This remarkable development traces its formal roots to Grameen Bank but today encompasses a diverse ecosystem of institutions. The four dominant players—Grameen Bank, BRAC, ASA, and TMSS—together reach over 30 million clients, primarily women, across more than 80,000 villages. Beyond these giants, hundreds of smaller MFIs and community groups contribute to financial inclusion, poverty reduction, and rural development.

3.1. Grameen Bank: The Pioneer of Group Lending

Founded in 1983 by Dr. Muhammad Yunus, Grameen Bank grew from a pilot loan of $27 in 1976 to a nationwide institution serving more than 9 million borrowers, 97% of whom are women, in over 81,000 villages. Its mission is to alleviate poverty through group-based microcredit combined with social development.

Lending Methodology

- Group Solidarity: Borrowers form self-help groups of five. Each member’s borrowing capacity depends on the group’s collective creditworthiness.

- Weekly Repayments: Small, frequent repayments build discipline and reduce default risk.

- No Physical Collateral: Trust and peer pressure replace conventional collateral.

Social Dimension: “16 Decisions”

Grameen borrowers commit to sixteen social pledges—covering sanitation, education, healthcare, family planning, and environmental stewardship—that extend the impact of microcredit into community welfare.

Achievements and Innovations

- Corporate Structure: Legally structured as a bank, Grameen combines regulatory oversight with social mission.

- Global Replication: Its model has inspired microfinance programs in over 60 countries.

- Product Diversification: Beyond core credit, it offers housing loans, education loans, and small savings products.

Key Challenges and Solutions

- Over-Indebtedness: Grameen’s group lending model includes peer monitoring, where members ensure that no one over-borrows. Additionally, Grameen tracks borrowers’ histories through integrated MIS (Management Information Systems) and avoids issuing multiple concurrent loans.

- Sustainability: Grameen maintains sustainability by diversifying its loan portfolio—offering housing, education, and solar loans—ensuring stable cash flow and borrower loyalty.

- Digital Adoption: To improve efficiency and expand access, Grameen has started piloting mobile loan repayment systems, reducing administrative burden and client travel costs.

- Market Competition: In response to rising competition, Grameen focuses on building strong community relationships and tailoring services to low-income women who are often excluded from commercial lenders.

3.2. BRAC: The Integrated “Graduation” Approach

Established in 1972 as the Bangladesh Rural Advancement Committee, BRAC has evolved into the world’s largest NGO, with programs across Asia and Africa. Its microfinance arm serves over 7 million clients, primarily women, leveraging a “graduation” approach that integrates financial services with social support.

The Graduation Model

- Asset Transfer: Ultra-poor households receive assets (e.g., livestock) to generate income.

- Consumption Support: Temporary stipends cover food and basic needs until enterprises become sustainable.

- Skills Training: Livelihood, financial literacy, and health education strengthen capabilities.

- Savings and Credit: After initial support, participants move into standard microfinance products, ensuring continuity.

Social Services Integration

BRAC embeds microfinance within its broader health, education, and legal services, creating synergies that accelerate poverty reduction.

Achievements and Innovations

- High Graduation Rates: Studies show over 90% of participants maintain higher and more stable incomes.

- Global Network: BRAC’s model operates in 15 countries, tailoring approaches to local contexts.

- Digital Finance: Recent pilots in mobile money and e-wallets are expanding access and reducing transaction costs.

Key Challenges and Solutions

- Scalability vs. Impact: The graduation model is resource-intensive. To tackle this, BRAC phases support based on household need and uses data-driven targeting to identify the ultra-poor most likely to benefit.

- Over-Indebtedness: BRAC trains clients in financial literacy and household budgeting before they graduate to microloans, reducing the risk of taking on unsustainable debt.

- Digital Divide: BRAC partners with telecom providers to offer mobile wallets and digital financial literacy training, expanding access to digital payments even in remote areas.

- Sustainability: BRAC cross-subsidizes high-touch programs with income from more stable microfinance segments and donor-supported innovation labs.

3.3. ASA: The Cost-Efficient Growth Engine

Founded in 1978, the Association for Social Advancement (ASA) emphasizes cost efficiency, simplicity, and replicable processes. With over 6.5 million active clients, ASA is the second-largest MFI in Bangladesh by outreach.

Standardized, Low-Cost Model

- Uniform Products: ASA offers a narrow range of loan sizes and tenors, streamlining operations.

- Lean Operations: Minimal overhead—standard branch layouts, uniform staffing, and rigorous performance metrics—drive down administrative costs.

- High Productivity: Loan officers handle a high number of clients, boosting outreach per staff.

Achievements and Innovations

- Financial Sustainability: ASA achieved operational self-sufficiency in the early 2000s and has maintained profitability while expanding.

- Technology Adoption: Introduction of biometric client identification and digital loan tracking enhances accuracy and reduces fraud.

- Rapid Expansion: With its low-cost model, ASA opens new branches quickly to reach underserved communities.

Key Challenges and Solutions

- Client Overload: To prevent loan officers from overextending, ASA uses digital dashboards and performance monitoring to balance workload, ensuring borrowers get adequate attention.

- Lack of Social Services: While ASA doesn’t provide extensive non-financial services, it partners with NGOs and government agencies to offer optional health or training support.

- Sustainability: ASA maintains strong financial health through high repayment rates (around 98%) and low operating costs. It also reinvests profits to expand services rather than relying on external funding.

- Digital Innovation: ASA has rolled out mobile data collection tools and biometric ID systems for improved borrower verification and loan disbursement accuracy.

3.4. TMSS: Women-Focused and Diversified Services

Thengamara Mohila Sabuj Sangha (TMSS), founded in 1990, focuses on women’s empowerment through microfinance, supplemented by health, education, and training programs. TMSS serves over 1 million clients across rural Bangladesh.

Women-Centric Model

- Female Staff and Leadership: TMSS employs a majority-female workforce, fostering trust and cultural sensitivity.

- Tailored Products: Loans and savings products address women’s specific needs—home improvement, child education, and small enterprise capital.

Integrated Services

- Health: Mobile clinics and health education sessions target maternal and child health.

- Education: Scholarships, literacy classes, and school construction projects support children from borrower households.

- Skills Training: Vocational courses in tailoring, handicrafts, and agriculture diversify income sources.

Achievements and Innovations

- Community Development: TMSS’s Village Development Committees empower borrowers to identify and address local needs.

- Digital Tools: Pilots of mobile financial services and digital training modules are improving efficiency and outreach.

Key Challenges and Solutions

- Scale vs. Service Quality: TMSS decentralizes management, empowering regional offices to adapt services to local needs while maintaining national standards through audits and feedback systems.

- Funding for Social Programs: TMSS blends income from microfinance with grants and CSR funds from corporate partners to support its health and education initiatives.

- Digital Literacy Barriers: TMSS integrates mobile training centers and community facilitators who help women clients navigate mobile banking and digital ID platforms.

- Market Competition: By focusing on female-centric services—such as maternal health loans and family education support—TMSS differentiates itself from generic MFIs.

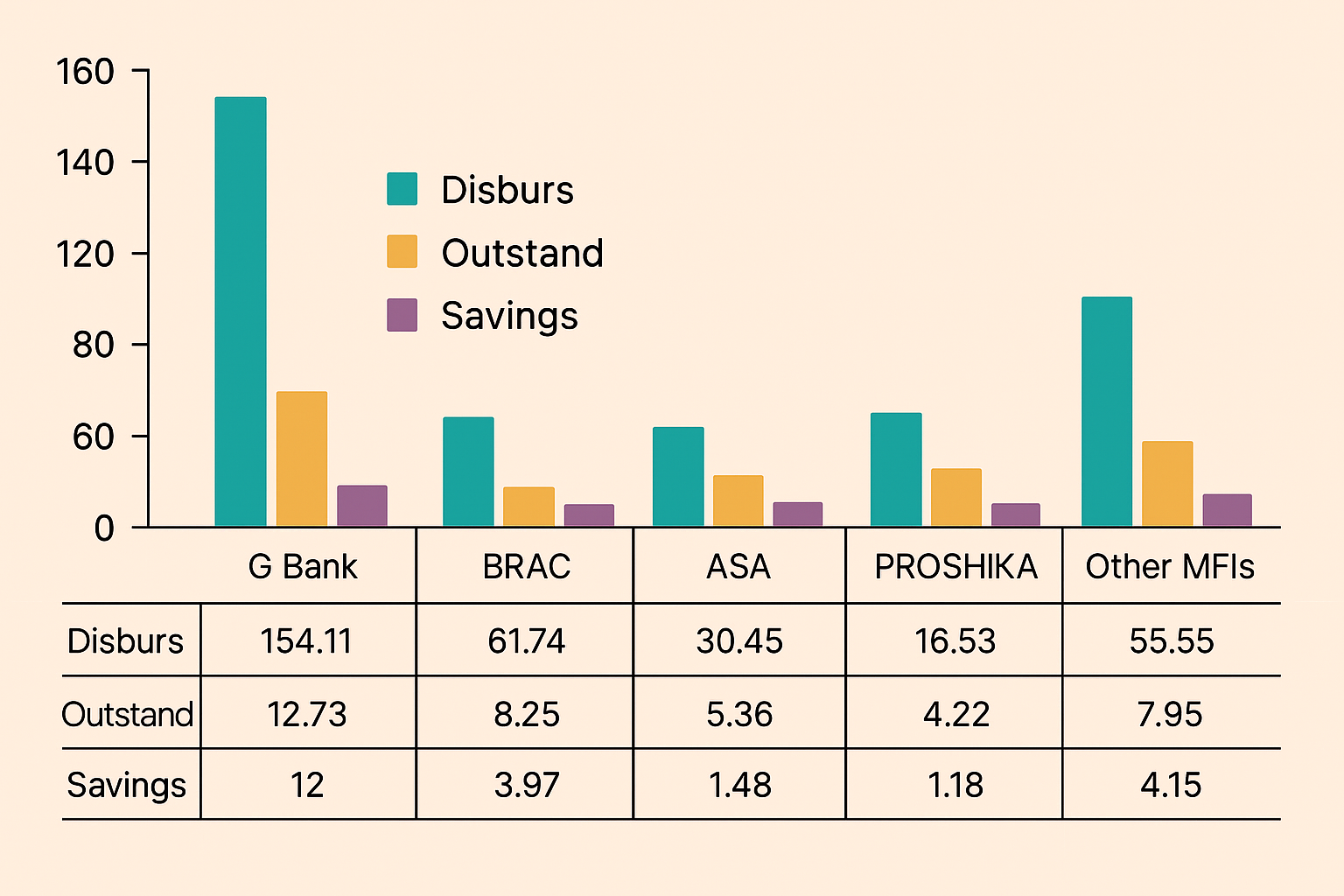

3.5. The Broader Microfinance Ecosystem

Beyond these leading MFIs, Bangladesh hosts over 700 licensed microfinance providers, including:

- Shakti Foundation for Disadvantaged Women

- Uddipan

- Jagorani Chakra Foundation

- Numerous community-based self-help groups (SHGs) and cooperatives

Collectively, these organizations serve over 35 million clients, offering various combinations of credit, savings, insurance, and social services. They compete and collaborate in a mature market regulated by the Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA), established in 2006 to ensure transparency, consumer protection, and practitioner accountability.

Tackling System-Wide Challenges:

- Overlapping Borrowers: The Microcredit Regulatory Authority (MRA) mandates the use of Credit Information Bureau (CIB) data to identify overlapping borrowers.

- Technology Integration: MFIs are adopting mobile money platforms like bKash to streamline disbursements and repayments.

- Client Protection: Many MFIs follow the Smart Campaign’s client protection principles, focusing on ethical lending and transparent communication.

- Financial Inclusion for the Ultra-Poor: Smaller MFIs often use community-based targeting and work with local NGOs to reach those untouched by the big four institutions.

Bangladesh’s microfinance sector is one of the most mature and impactful in the world. Institutions like Grameen Bank, BRAC, ASA, and TMSS have not only revolutionized rural finance but also evolved sophisticated mechanisms to tackle challenges like over-indebtedness, digital exclusion, and sustainability. By integrating financial services with social development, these organizations have lifted millions out of poverty.

Read more: 2024–2025 Fintech Outlook: Exploring Landscape & Opportunities in Bangladesh

4. Microfinance Models Used in Bangladesh

Bangladesh is widely recognized as the birthplace of modern microfinance, pioneering innovative models that have been replicated globally. Over the decades, Bangladeshi microfinance institutions (MFIs) have developed and refined several distinct models to serve the poor, particularly women, by providing small loans, savings opportunities, and insurance products tailored to their unique needs. These models are designed not only to improve financial access but also to build community solidarity, ensure loan repayment, and support economic resilience. The following are the key microfinance models employed in Bangladesh, along with examples demonstrating their success.

4.1. Group Lending Model

One of the most famous and foundational microfinance models in Bangladesh is the Group Lending Model, popularized by the Grameen Bank. This approach revolves around forming small groups, typically composed of five members, who are jointly responsible for each member’s loan repayment.

How it Works:

Each borrower takes a loan individually, but the entire group is collectively accountable. If one member fails to repay, the group members face pressure to cover the default or encourage repayment. This social collateral replaces physical collateral, which poor borrowers usually lack.

Benefits:

- Social Accountability: Peer pressure within the group motivates timely repayment.

- Lower Risk: Group members screen each other to ensure only trustworthy members receive loans.

- Empowerment: Women in particular gain social support and encouragement through group solidarity.

Example: Grameen Bank, founded by Dr. Muhammad Yunus in 1983, successfully used this model to provide microloans to over 9 million borrowers, with 97% women. This method drastically reduced default rates and encouraged financial discipline among marginalized rural women. The weekly meetings fostered not only loan repayments but also social awareness on hygiene, education, and family planning (Grameen’s “16 Decisions”).

4.2. Village Banking Model

The Village Banking Model is another community-centered approach, often used by organizations like BRAC and several smaller NGOs.

How it Works:

Village banks are self-managed community groups of about 20 to 40 members. These groups operate as informal community banks, pooling their savings and revolving loans among members.

- MFIs or donors provide seed capital as the initial loan fund.

- Members meet regularly to manage loans, repayments, savings, and group governance.

- The group maintains autonomy, electing leaders and setting lending policies.

Benefits:

- Local Ownership: Village members directly manage funds, which builds trust and accountability.

- Savings Mobilization: Encourages habitual savings alongside borrowing.

- Flexibility: Members decide lending terms based on community needs.

Example: BRAC has employed the village banking model as part of its comprehensive microfinance strategy. This model integrates financial services with social programs like health, education, and legal aid. Village banks have empowered rural women to collectively manage resources and improve household income, helping BRAC reach over 7 million borrowers.

4.3. Flexible Repayment Programs

Recognizing the vulnerability of poor borrowers to natural disasters and seasonal income fluctuations, leading MFIs such as BRAC and Grameen Bank have introduced Flexible Repayment Programs.

How it Works:

These programs allow borrowers to adjust their repayment schedules during times of hardship such as floods, cyclones, or droughts, common in Bangladesh.

- Borrowers can delay payments without penalty or reduce installments temporarily.

- MFIs offer rescheduling or loan restructuring to avoid defaults.

Benefits:

- Risk Mitigation: Helps borrowers avoid over-indebtedness during crises.

- Sustained Access: Borrowers remain eligible for future loans despite temporary difficulties.

- Community Stability: Prevents negative shocks from cascading through poor communities.

Example: During the devastating floods of 2017, BRAC implemented flexible repayment options allowing thousands of borrowers to pause or reduce payments. This approach prevented widespread defaults and enabled quicker recovery. Similarly, Grameen Bank has employed similar policies following natural disasters, maintaining strong borrower relationships.

4.4. Micro-Savings and Insurance

Over time, most MFIs in Bangladesh have expanded beyond credit to offer micro-savings and micro-insurance products to improve client resilience.

Micro-Savings:

- Encourage clients to save small amounts regularly, fostering financial discipline and a safety net.

- Savings accounts are often mandatory for loan eligibility, reducing risks for both borrower and lender.

Micro-Insurance:

- Includes health, life, and crop insurance tailored for low-income populations vulnerable to shocks.

- Reduces the financial impact of illness, death, or crop failure on poor households.

Renewable Energy Loans (Grameen Shakti):

An innovative example of blending microfinance with social impact is Grameen Shakti, a subsidiary of Grameen Bank focusing on renewable energy.

- Provides loans specifically for solar home systems and other clean energy products.

- Targets off-grid rural households lacking electricity, enabling access to affordable and sustainable energy.

- Loan repayments are structured to be affordable relative to the borrower’s income and energy savings.

Impact:

Grameen Shakti has installed solar home systems for over 1.8 million households in Bangladesh, significantly improving quality of life by providing clean, reliable electricity, reducing kerosene use, and promoting environmental sustainability.

Together, these models have helped millions of Bangladeshi households access credit, build assets, and increase resilience. The ongoing innovation within these frameworks, especially with the integration of digital finance and green energy loans, positions Bangladesh’s microfinance sector as a global model for inclusive financial services.

5. Economic Impact of Microfinance in Bangladesh

Microfinance has had a transformative effect on Bangladesh’s economy and society, particularly by empowering marginalized communities, reducing poverty, and fostering sustainable development. Since its inception in the late 1970s, microfinance has evolved into a critical tool for economic upliftment, especially among women and rural households. The following are the key economic impacts observed in Bangladesh, supported by concrete examples.

5.1. Poverty Reduction

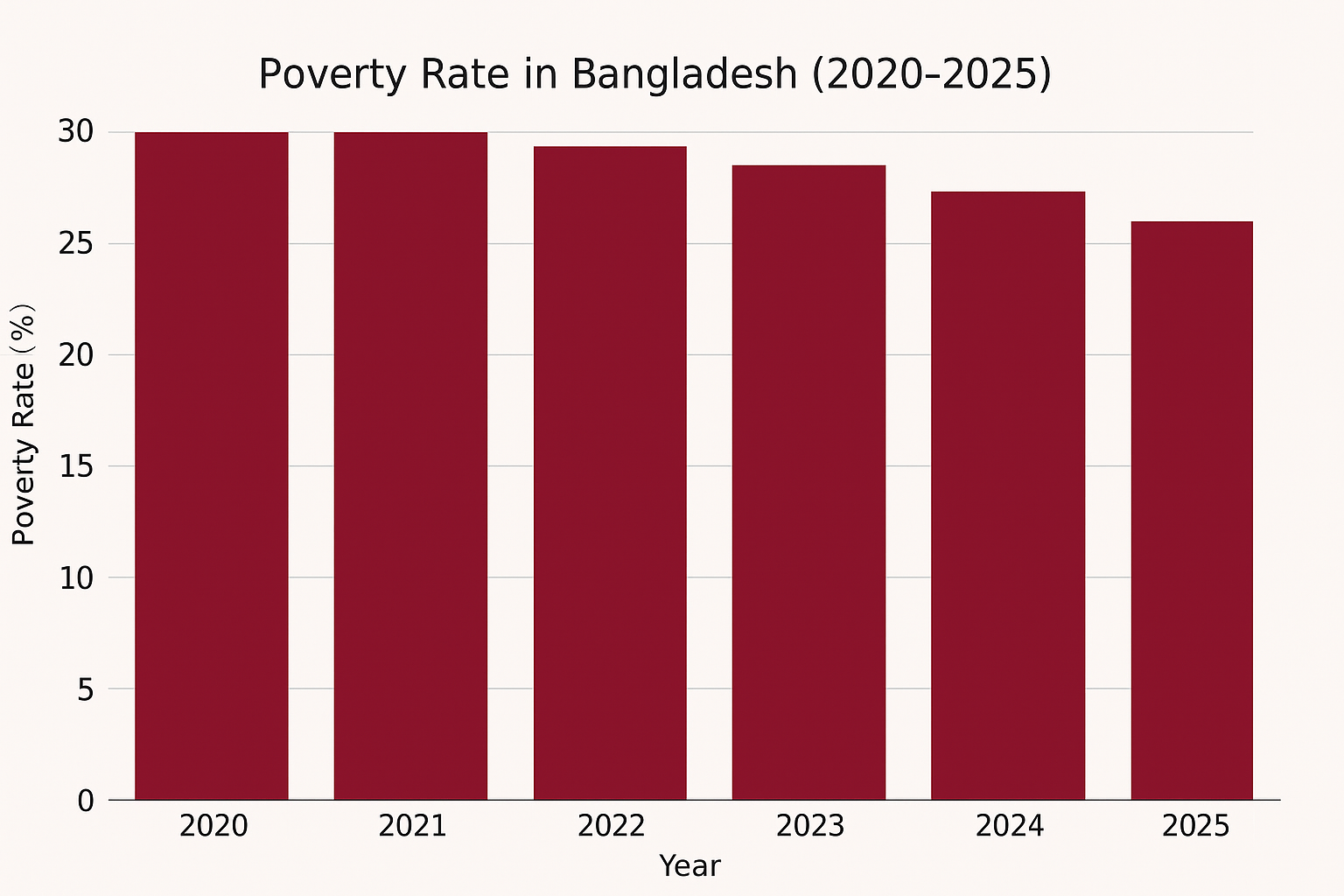

One of the most significant outcomes of microfinance in Bangladesh has been its contribution to poverty alleviation. According to research by the World Bank and various academic studies, microfinance initiatives have helped reduce poverty by approximately 1 to 2 percent annually in the country.

- Sustained Income Growth: Borrowers who engaged in multiple loan cycles have been able to steadily increase their household income. This growth is primarily due to the reinvestment of earnings into income-generating activities such as farming, small trading, and handicrafts.

- Improved Food Security: Access to microloans enables families to purchase better quality seeds, livestock, and farming inputs, leading to enhanced agricultural productivity and more stable food supplies.

- Asset Accumulation: Over time, borrowers accumulate productive assets like livestock, sewing machines, or small equipment, which further contribute to economic resilience.

A study by the Grameen Bank showed that families who received microfinance loans invested in poultry and livestock, significantly increasing their income and reducing vulnerability to economic shocks. These investments also allowed families to improve their housing conditions and save for future needs.

5.2. Women Empowerment

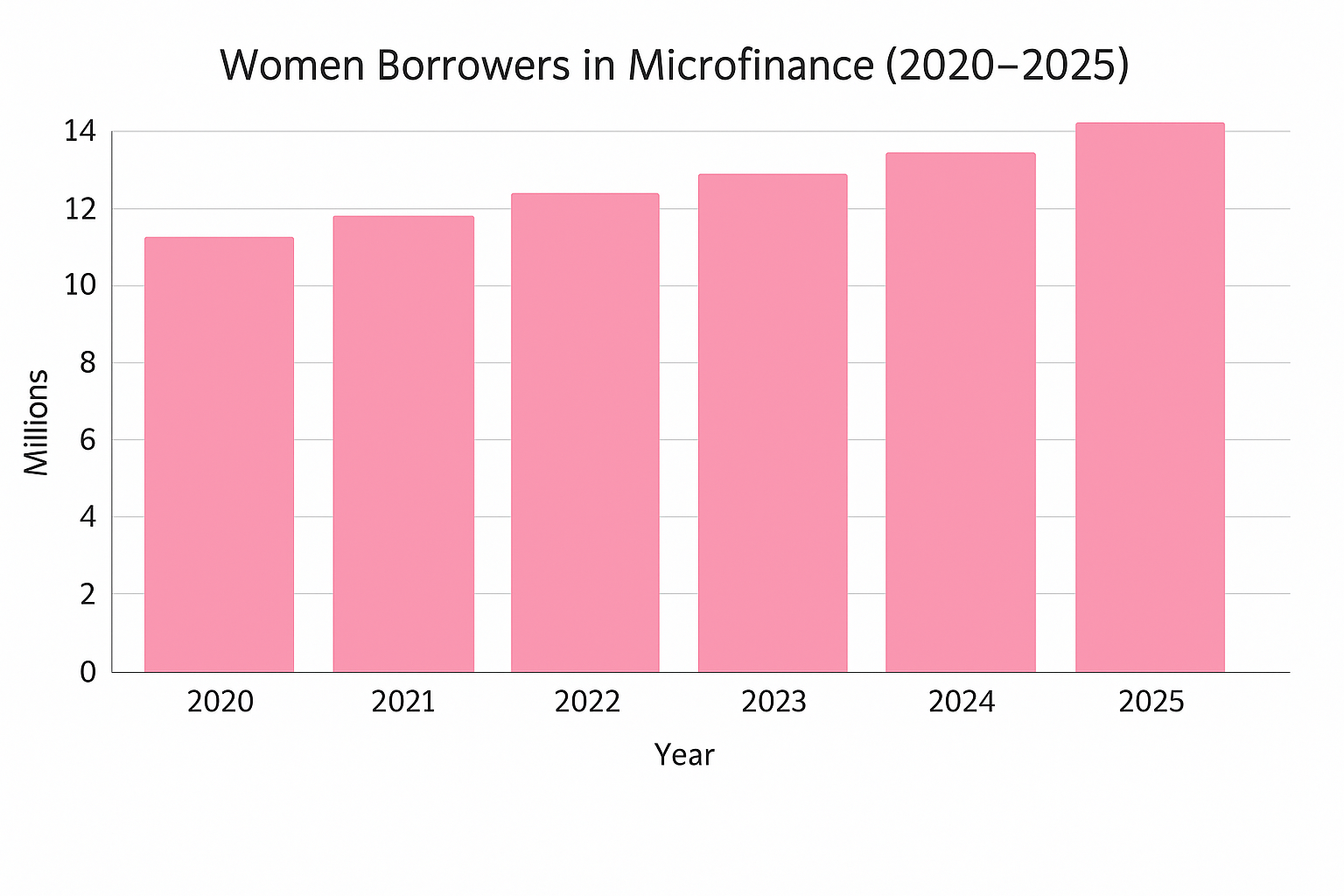

Microfinance in Bangladesh predominantly targets women, who constitute over 90% of borrowers. This focus has led to substantial social and economic empowerment for women across the country.

- Greater Mobility and Independence: With their own source of income, women gain mobility and the ability to participate more actively in household and community decisions.

- Decision-Making Power: Financial independence boosts women’s status within families, allowing them to influence critical decisions about children’s education, healthcare, and household spending.

- Community Participation: Women borrowers often become community leaders or take part in local governance and social initiatives.

- Integrated Social Programs: Many MFIs link credit services with health education, legal aid, and literacy programs, which collectively improve women’s social standing.

BRAC’s microfinance program pairs loans with health and education services. Women borrowers in rural Bangladesh have reported increased confidence and leadership roles within their communities, which in turn fosters gender equality and social cohesion.

5.3. Entrepreneurship and Job Creation

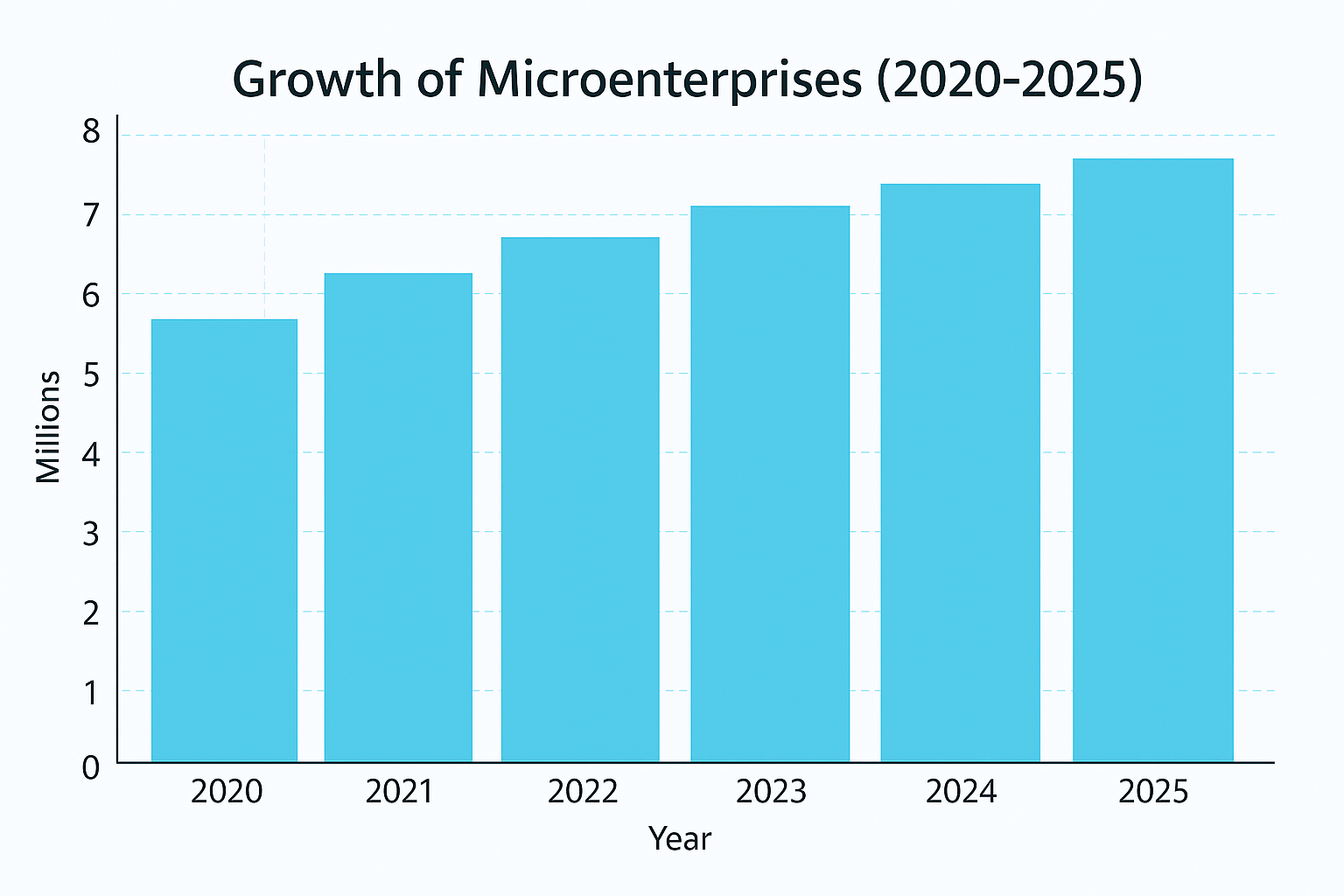

Microfinance has catalyzed entrepreneurial activities at the grassroots level, fostering job creation and economic diversification in rural and urban Bangladesh.

- Microenterprise Establishment: Borrowers start businesses in sectors such as tailoring, poultry farming, handicrafts, and small-scale agriculture, providing goods and services locally.

- Employer Creation: Many micro-entrepreneurs expand their operations to the point where they hire others, shifting from wage earners to employers.

- Reduced Seasonal Dependency: By generating alternative income sources, microfinance reduces borrowers’ reliance on seasonal wage labor, which is often precarious and poorly paid.

A woman in rural Bangladesh used a microloan from ASA to start a tailoring business, which grew to employ several local women. This business not only generated steady income but also fostered skill development among its employees, contributing to community economic development.

5.4. Health and Education

Microfinance influences household investments beyond income generation, particularly improving health and education outcomes.

- Sanitation and Nutrition: With better financial resources, families invest in clean water, improved sanitation facilities, and nutritious food, enhancing overall health standards.

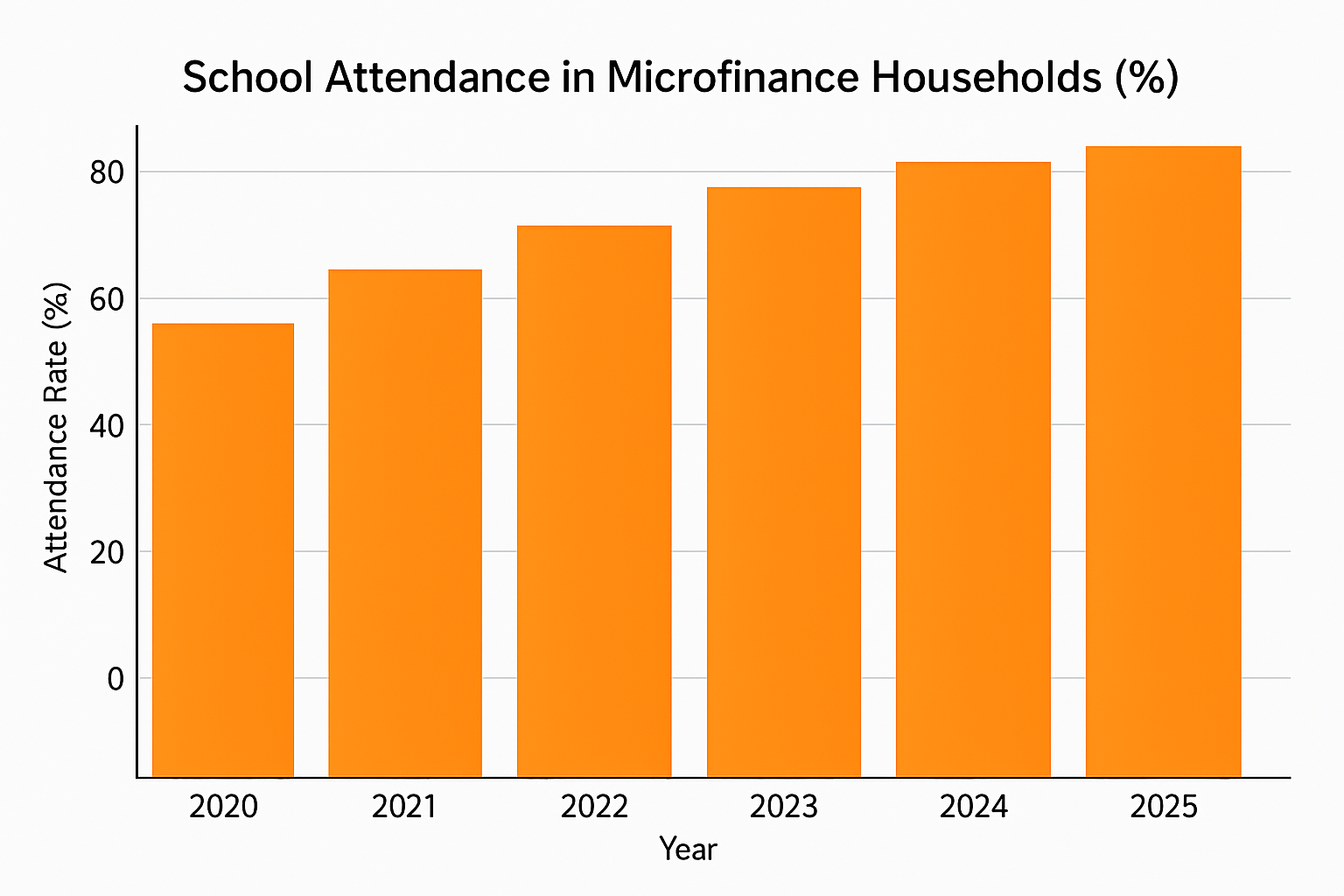

- Educational Investments: Borrowers prioritize their children’s education, often sending them to school and purchasing educational materials.

- Scholarships and Support: Organizations like Grameen and BRAC provide scholarships and educational support programs targeting the children of microfinance clients, helping reduce dropout rates and improve literacy.

Grameen Bank’s scholarship program has supported thousands of children from borrower families, enabling them to continue education through secondary and higher levels. The program’s success is reflected in higher school attendance rates in microfinance participant households compared to non-participants.

5.5. Social Capital Formation

Microfinance’s group lending approach builds strong community networks and social capital, which have positive spillover effects beyond financial transactions.

- Community Bonding: Group meetings foster trust, cooperation, and mutual support among members.

- Collective Action: Borrowers often come together to respond to local challenges such as natural disasters, organizing clean-up campaigns, and raising awareness on health and hygiene.

- Social Safety Nets: These networks provide informal support systems, such as helping members in times of crisis or pooling resources for communal benefits.

During the 2007 floods in Bangladesh, microfinance groups mobilized to provide emergency relief and support rebuilding efforts in affected villages. The strong social ties built through regular meetings allowed rapid and coordinated community responses, minimizing the disaster’s long-term impacts.

The economic impact of microfinance in Bangladesh is profound and multifaceted. By reducing poverty, empowering women, encouraging entrepreneurship, improving health and education, and building social capital, microfinance institutions have contributed significantly to the country’s sustainable development. These achievements are grounded in innovative, inclusive financial models that continue to evolve, ensuring that microfinance remains a vital catalyst for economic transformation in Bangladesh.

6. Innovations and the Future of Microfinance in Bangladesh

As the birthplace of institutionalized microfinance, Bangladesh continues to evolve and innovate in its approach to financial inclusion. While the traditional model of microcredit laid the foundation for empowering millions, emerging technologies, environmental concerns, and the need for deeper social impact have catalyzed new directions in the sector. Today, Bangladeshi microfinance institutions (MFIs) are no longer just loan providers; they are comprehensive platforms for economic empowerment, social change, and sustainable development. This section highlights the key innovations driving the future of microfinance in Bangladesh and their potential to deepen financial resilience.

6.1. Digital Microfinance: Revolutionizing Access and Efficiency

One of the most transformative innovations in Bangladesh’s microfinance sector is the adoption of digital financial services. The widespread use of mobile phones, mobile financial service (MFS) platforms like bKash and Nagad, and increased internet penetration have made it possible for even the most remote borrowers to access financial services efficiently.

- Mobile Banking Integration: MFIs now disburse loans and collect repayments through mobile wallets, eliminating the need for time-consuming in-person transactions. Clients receive funds directly into their digital accounts, enhancing transparency and reducing delays.

- Biometric Verification and e-KYC: The introduction of electronic Know Your Customer (e-KYC) systems and biometric authentication ensures secure client onboarding. These innovations reduce identity fraud and ensure accurate targeting.

- Cost and Time Efficiency: Digital systems reduce operational costs for MFIs and minimize travel expenses for clients, making microfinance more sustainable and scalable.

Grameen Bank has partnered with mobile operators to enable mobile repayments, resulting in higher repayment rates and increased client satisfaction. In flood-prone areas, digital disbursement ensures timely access to emergency funds.

6.2. Microinsurance and Pension Schemes: Protecting Against Future Risks

Microfinance is expanding beyond loans to include risk-mitigation tools like insurance and pension schemes. These services provide critical financial buffers to poor households vulnerable to illness, crop failure, or old age.

- Crop and Health Insurance: MFIs now offer microinsurance policies tailored for low-income individuals, covering health emergencies, livestock loss, and crop damage due to natural disasters.

- Retirement Savings: Pension products are being piloted to help informal workers and the self-employed save for old age, a segment largely ignored by traditional financial institutions.

- Bundled Services: Insurance products are often bundled with loans or savings schemes to ensure widespread adoption and to reduce administrative burdens.

BRAC’s collaboration with insurance providers has enabled rural clients to enroll in health and life insurance for nominal premiums. These programs have proven crucial in helping families recover after health emergencies or deaths of breadwinners.

6.3. Social Enterprise Integration: Creating Sustainable Markets

Bangladesh’s microfinance sector is increasingly being linked with social enterprises that provide market linkages, value chains, and income stability. Rather than simply offering loans, MFIs now connect borrowers to demand-driven markets.

- Aarong and BRAC Enterprises: BRAC’s flagship retail chain Aarong sources crafts, textiles, and other products from women borrowers and rural artisans, providing them with reliable markets and fair prices.

- Value Chain Finance: MFIs also invest in training and logistics support, enabling borrowers to meet market quality standards and scale up production.

- Income Stability: This model reduces the risk of market saturation and ensures that microenterprise activities are economically viable in the long term.

A female borrower from Manikganj trained in block printing through BRAC’s program now supplies products to Aarong. Her income has tripled, and she has hired two assistants from her community, showing the multiplying effect of market integration.

6.4. Green Microfinance: Financing a Sustainable Future

Environmental sustainability has become a key concern for microfinance institutions in Bangladesh, especially given the country’s vulnerability to climate change. Green microfinance aims to fund clean technologies that improve living conditions and reduce environmental harm.

- Grameen Shakti: A pioneer in green microfinance, Grameen Shakti provides loans for solar home systems, bio-gas digesters, and improved cookstoves. These solutions promote renewable energy and reduce reliance on fossil fuels and traditional biomass.

- Eco-friendly Enterprises: MFIs now support businesses that promote recycling, organic farming, and environmentally-friendly products, aligning income generation with ecological stewardship.

In rural Gaibandha, Grameen Shakti-financed solar panels now power schools and small shops, reducing kerosene use and health hazards from smoke. Families report better lighting, improved study conditions for children, and lower energy expenses.

6.5. Targeting the Ultra-Poor: Graduation Approach

Recognizing that traditional microfinance does not effectively serve the ultra-poor, BRAC developed the Ultra-Poor Graduation Model, which addresses extreme poverty through a multi-pronged approach.

- Asset Transfer: Families receive a productive asset such as livestock or tools rather than a loan, helping them build initial economic capacity.

- Stipends and Training: Alongside assets, BRAC provides a small stipend, training in asset management, and health support, ensuring participants can succeed without falling into debt.

- Financial Inclusion: Once stable, beneficiaries are integrated into the mainstream microfinance system, taking loans to grow their businesses.

This model has proven so effective that it is now replicated in over 40 countries by organizations such as the World Bank, UNDP, and governments seeking to end extreme poverty. A widow in Kurigram received a cow and training through the graduation program. Within 18 months, she had sold milk to neighbors, bought another calf, and enrolled in a microloan program to start a small grocery business.

Bangladesh remains a global leader in microfinance innovation. With digital tools, green finance, insurance, social enterprises, and tailored programs for the ultra-poor, the sector is not only surviving—it is thriving and evolving to meet the changing needs of the people it serves.

7. Conclusion

Bangladesh’s microfinance sector is not only a national asset but a global inspiration. What began as a modest experiment in Jobra village has grown into a powerful engine of empowerment, resilience, and inclusive growth. While challenges persist—from regulatory gaps to over-indebtedness—the continuous innovation, social mission, and adaptability of MFIs in Bangladesh ensure that the country remains at the forefront of microfinance evolution. As digital technology and financial inclusion converge, Bangladesh is poised to enter a new era of smart, ethical, and impact-driven microfinance—one that not only alleviates poverty but builds a more equitable and prosperous society.