Tanguar Haor in crisis due to biodiversity loss, overfishing, and ecological damage. An urgent conservation project launched by UNDP and the Bangladesh government.

Introduction: A Paradise in Peril

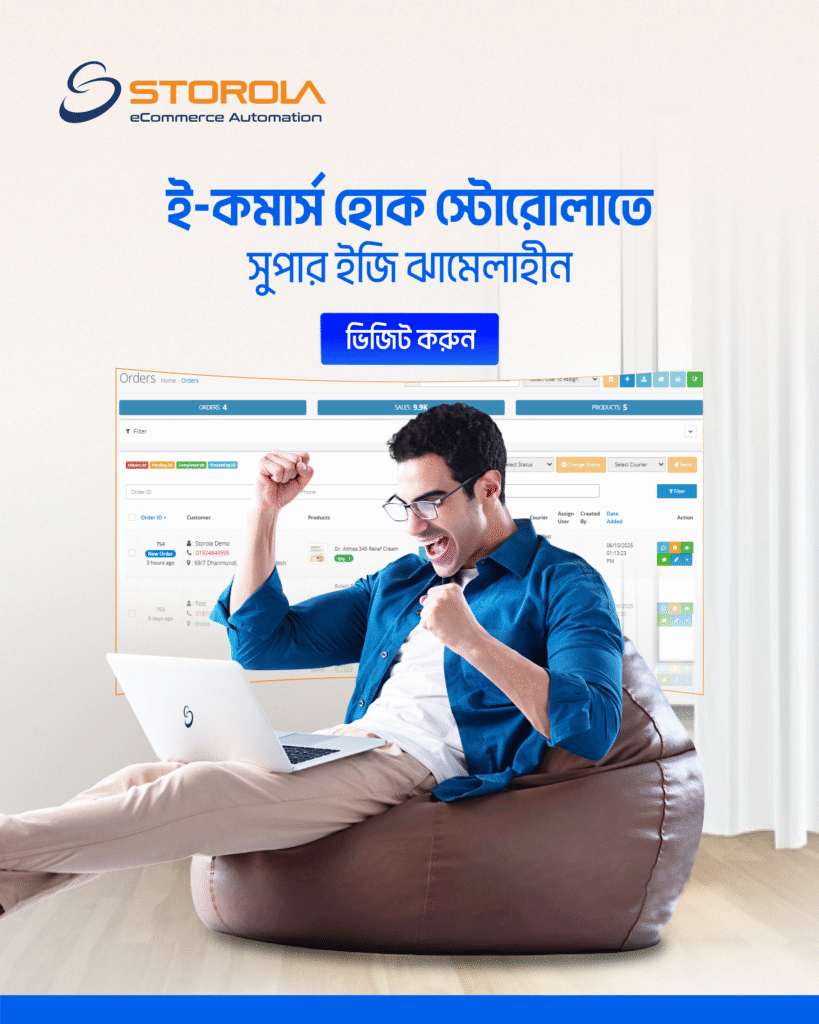

Tanguar Haor, located in Sunamganj district of northeastern Bangladesh, is one of the country’s most significant wetlands. Recognized as Bangladesh’s second Ramsar site, this vast ecosystem once thrived with over 140 species of freshwater fish, migratory birds, and lush swamp forests.

The Haor supports a rich diversity of flora and fauna, including numerous species of fish, birds, and aquatic plants. It serves as a crucial habitat for migratory birds and is home to several endangered wildlife species, making it a vital ecological hotspot.

It served as a life source for more than 40,000 people directly dependent on fishing, farming, and seasonal tourism. But that paradise is now under serious threat.

A recent investigative report by Prothom Alo, titled “আগে মাছের অভাব ছিল না, এখন চাষের পাঙাশ কিনে খাই” (Once There Was No Fish Shortage, Now We Buy Farmed Pangas), paints a heartbreaking picture of declining biodiversity, disappearing fish stocks, and a struggling local population.

The Melody of Life Fades Despite Ramsar Recognition

Tanguar Haor, Bangladesh’s second Ramsar site, was once a sanctuary of life, abundance, and natural beauty. It wasn’t merely a gift of nature, it was intricately woven into the livelihoods of thousands of people. But today, the haor paints a grim picture melancholic, neglected, and endangered.

Over the past 22 years, since the lease-based fishing system was abolished, the government and various organizations have taken on numerous development plans. Yet, the reality shows that most of these efforts have remained confined to paper. On the ground, there is neither adequate monitoring nor structured management. As a result, exploitation has replaced conservation.

At the very entrance of the haor, one is greeted by rows of houseboats, a symbol of chaos in what was once serene nature. The roar of generators runs nonstop, and plastic, polythene, and various wastes are dumped indiscriminately. These scenes are clear signs that this paradise is no longer safe.

This mismanagement is having a devastating effect on the haor’s biodiversity. Where once around 200,000 migratory birds visited each year, this year has seen the lowest number in recorded history. Who is responsible for this disaster? Is it administrative inaction, public apathy, or a collective failure?

Tanguar Haor was once declared Bangladesh’s most biodiverse wetland after the Sundarbans. In 2000, it gained international recognition through the Ramsar Convention. But sadly, this honor hasn’t translated into real protection. There is a lack of preservation mechanisms, minimal community involvement, and no administrative accountability.

According to environmentalists and locals, Tanguar Haor has become a “priceless orphan.” Everyone is destroying it in their own way some cutting down trees, some looting bird eggs, others choking its waters with waste. Yet this very haor could have played a vital role in the country’s climate stability, food security, and ecological balance.

Current Crisis

Despite its importance, Tanguar Haor faces a rapid decline in biodiversity primarily due to human-induced pressures:

-

Overfishing and the use of illegal, destructive fishing methods threaten fish populations.

-

Illegal hunting has contributed to the decrease of bird and wildlife species.

-

Habitat destruction from encroachment and pollution is severely damaging the ecosystem.

These factors collectively undermine the ecological integrity of the wetland.

Impact on Local Communities

Thousands of people who live around Tanguar Haor depend on fishing and farming to survive. But now, fish are hard to find. This means less food for families and less money to earn.

Many are struggling to feed their children or pay for daily needs. The loss of people’s way of life is the catastrophe, not simply the environment. Fishing and farming were the two main sources of food and income. But now, the situation has changed drastically.

Read More: The Revolutionary iPhone 17 is Coming – Here’s What to Expect!

How the Tanguar Haor Crisis is Changing Lives

Tanguar Haor, once full of life, is now fading away. The people here used to depend on its water, fish, and paddy fields for their survival. But today, even after casting their nets, fishers return empty-handed.

Places like Alangdowar, once known for Chitol fish, have now become silent and lifeless. Local fishers say, “There’s no fish, only water and disappointment.”

In the past, people used to protect fish habitats by placing bamboo and branches in the water. Those community-led practices have now stopped. Instead, harmful tools like “China Duwari” nets are widely used catching even the smallest fish. Worse, electric shock methods are being used, killing not just fish but also many other aquatic animals.

In this way, the life of the haor is disappearing, and with it, people’s livelihoods are collapsing. Families who once ate fresh native fish now buy farmed pangas or tilapia from the market if they can afford it.

Fishing has dropped, and farming is now full of risks. Rice cultivation in the haor depends heavily on rainfall. A single storm or flood can wipe out an entire year’s food and income.

According to the local fisheries department, there’s no specific data on fish production in Tanguar Haor. Their general record shows that in 2021–22, Sunamganj district produced about 109,517 metric tons of fish, with 32,096 metric tons from haor areas. But local fishers disagree. They say native fish have almost vanished. Now, farmed fish like pangas and tilapia are sold in the markets, replacing the once-rich variety of local fish.

Some locals worked as sand laborers on the Jadukata River or carried coal from the border, but those jobs are fading too. Since 2016, coal import has become irregular, and machines have replaced human labor on the riverbanks.

After the devastating crop failure in 2017, many families had to leave their villages in search of work. Some who stayed behind have ended up in dangerous smuggling work near the border to survive.

Jofura Begum, a 75-year-old local resident, said with sorrow:

“When I used to bathe, fish touched my feet. At night, I couldn’t sleep because of birds’ wings flapping. We had no rice sometimes, but fish was never a problem. Now, we have to buy farmed fish to eat.”

Tanguar Haor was the people’s identity, hope, and means of subsistence, it is more than just a marsh. That life is now in a precarious position.

China Duari Nets: A Growing Threat to Aquatic Life in Bangladesh

Photo: The Daily Morning Glory

Photo: The Daily Morning Glory

China Duari nets also known as fine-mesh fish traps are becoming an alarming threat to Bangladesh’s aquatic biodiversity. These nets, much finer than traditional current nets, are extremely effective at trapping not only fish but also countless small aquatic creatures like fry, frogs, and even fish eggs. Once something enters the net, it rarely escapes due to the tightly woven mesh.

Fishermen are increasingly turning to these nets because they can catch more fish with less effort. Despite being officially banned for production, marketing, and use, China Duari nets are still being set by the thousands each day in rivers and wetlands across regions.

This is leading to the mass destruction of mother fish and baby fish, and if the trend continues, Bangladesh may soon lose many of its native fish species. The wider aquatic ecosystem is also at risk Even though the law prohibits these nets, they are still being manufactured and sold under the radar.

In an interview with Voice7 News, Akhtar Hossain, Chairman of Bilchalan Union Council, said that-

“I issued a trade license to ‘Sithi Traders’ for the production and sale of fishing equipment. I didn’t know that Sushanta Haldar was using it to produce illegal China Duari nets.”

When questioned, Sushanta Haldar admitted:

“This is happening all over the place. We’re just doing a little. We started small in Bothor. We’re simply training people, this isn’t a full factory. The setup began before Eid-ul-Fitr. My brother-in-law Prakash Haldar is in charge of it.”

This casual attitude shows how deeply normalized the illegal practice has become and how urgently intervention is needed.

Unless strong actions are taken by local authorities and the Department of Fisheries, Bangladesh’s aquatic biodiversity will continue to suffer irreversible damage.

To address the harmful impact of China Duari nets and protect aquatic biodiversity in Bangladesh, a multi-layered, community-driven, and policy-enforced solution is needed.

To protect Bangladesh’s aquatic biodiversity and restore native fish populations, the following practical steps should be taken immediately:

1. Strict Enforcement of the Ban

The existing ban on the production, sale, and use of China Duari nets must be strictly enforced. Local authorities, including fisheries officers and law enforcement agencies, should conduct regular inspections in areas known for illegal net use and production.

2. Destroy Illegal Nets

Confiscated China Duari nets should be permanently destroyed to prevent them from returning to circulation. Legal actions should be taken against repeat offenders involved in manufacturing or using the nets.

3. Fisher Education and Awareness

Conduct nationwide awareness campaigns targeting fishermen, market traders, and net manufacturers to explain the ecological damage caused by these nets. Visual materials, local workshops, and radio announcements can help reach remote communities.

4. Promote Eco-Friendly Alternatives

Introduce and subsidize the use of traditional or scientifically-approved fishing nets that allow juvenile fish and non-target species to escape. Promoting sustainable fishing gear will help balance livelihood needs with conservation.

5. Community-Led Monitoring

Empower local fishing communities to monitor their water bodies. Forming “Community Watch” or “Eco-Fisher Groups” can help report illegal activities quickly, making conservation a shared responsibility.

6. Licensing Reforms

Local governments must revise the licensing system to ensure transparency. Trade licenses should be regularly reviewed, and the purpose of use must be strictly monitored to avoid misuse under general terms like “fishing equipment.”

7. Alternative Livelihood Support

Support fishers who rely on harmful practices by offering training in alternative income sources such as aquaculture, duck farming, eco-tourism, or handicrafts. This reduces dependency on harmful fishing methods.

8. Research and Data Collection

Invest in scientific studies to monitor the impact of these nets and measure biodiversity loss. This data will help in policy making and justifying budget allocations for conservation.

Perhaps this is a comprehensive framework for a solution.

Unregulated Houseboats Threaten Environment in Tanguar Haor

As the rainy season approaches, a growing number of houseboats are seen idly floating at the entrance of Tanguar Haor from Tahirpur. Some boats run noisy generators, others have kitchens actively in use, and many are simply waiting for the tourist rush.

Locals report that during monsoon, nearly 200 houseboats anchor in the Haor, and most of them dump their waste solid and liquid directly into the water.

The result is alarming. Loud music, bright lights at night, and rising luxury tourism are increasingly disturbing the natural ecosystem of the Haor, a designated Ramsar site known for its rich biodiversity.

Locals fear that the growing trend of spending nights on boats is putting wildlife, especially migratory birds and aquatic species, at risk. The houseboats waste disposal has become a public health concern.

Beyond the environmental impact, safety concerns are growing. Many tourists stay overnight in these boats during monsoon, despite limited oversight and emergency preparedness. Just recently, on May 31, a tourist houseboat named Rahabar caught fire in Tahirpur. All 12 tourists onboard narrowly escaped, raising questions about fire safety and regulation.

To address the issue, authorities are now working to bring all houseboats under a formal registration system. Meanwhile, on June 11, the local administration fined a tourist boat for playing loud music in the Haor.

Experts and locals alike suggest building eco-friendly alternatives such as small, regulated resorts or guesthouses in designated zones facilities that do not pollute or interfere with wildlife.

The Economic Cost of Houseboat Tourism in Tanguar Haor

While houseboat tourism in Tanguar Haor may appear to be a sign of growing rural enterprise and travel enthusiasm, its unchecked rise reveals deeper economic concerns specially for the local community and ecological sustainability.

Short-Term Gains, Long-Term Losses

Every monsoon, hundreds of houseboats arrive in Tanguar Haor, bringing in tourists from Dhaka and beyond. These houseboats generate income through:

-

Boat rentals and packages

-

Local transportation

-

Food supply and hospitality services

-

Tour guide employment

For boat owners and operators many of whom are investors from outside the region this is a profitable seasonal business. Some boats charge high fees, attracting affluent tourists and contributing to a booming private sector tourism model.

But the profit is not equally shared. Local people who have traditionally depended on fishing and farming are left struggling. The pollution and waste dumped into the Haor directly damage their access to clean water and natural resources, reducing fish stocks and threatening sustainable livelihoods.

Tanguar Haor: The Fight to Restore a Lost Paradise

Once upon a time, Tanguar Haor was a natural wonder which is filled with schools of fish swimming through the water, migratory birds dancing across the sky, and local communities building their lives around its blessings.

To protect this priceless wetland, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change of Bangladesh has joined hands with the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP). Funded by the Global Environment Facility (GEF), a new initiative was launched on May 22 “Community-Based Management of Tanguar Haor Wetland Ecosystem”, coinciding with the International Day for Biological Diversity.

However, this undertaking is a profoundly human effort rather than merely a technical conservation activity. Among its main objectives are:

-

Ensuring the sustainable use of the haor’s natural resources

-

Actively involving local communities

-

Restoring the rapidly disappearing aquatic forests and ecosystems

-

Creating alternative livelihood opportunities for local families

Speaking about this effort, UNDP Bangladesh’s Resident Representative, Stefan Liller, emotionally stated that “Tanguar Haor is not just a home to fish, but also to migratory birds and rich biodiversity. To protect such a treasure, local communities must be at the heart of our efforts.”

Today, as the water becomes polluted, fish stocks dwindle, and the livelihoods of farmers and fishers face growing threats. His initiative is a promise to the people whose lives depend on the haor, not just a plan.

If carried out correctly Perhaps one day the sound of birds will fill the air again, and the splashing of fish will return to the water. Tanguar Haor deserves to be a symbol of life once more than a quiet sanctuary of natural beauty and hope.

Environmental Damage = Economic Burden

Pollution from these houseboats, specially untreated sewage and food waste, degrades the water quality of the Haor. This leads to:

-

Decline in native fish population, affecting local fishing economy

-

Loss of biodiversity, damaging ecotourism potential in the long run

-

Health risks for local residents, leading to increased household medical costs

-

Reduced availability of clean water for domestic use

In economic terms, these hidden costs could outweigh the seasonal profits from houseboat tourism if not properly regulated. What appears to be a source of income could soon become a source of long-term loss for the community.

Missed Opportunities for Local Development

Local residents receive very little direct benefit from the luxury houseboat business. Most of the operators are from outside Sunamganj, meaning:

-

Capital flight occurs the bulk of the profits go back to Dhaka

-

Local labor is underutilized or employed in marginal roles

-

Local products (like fish or crafts) are not integrated into the tourist value chain

By contrast, a well-regulated eco-tourism model could create jobs in hospitality, transportation, retail, and environmental management for the local population. This would lead to inclusive economic growth, not just seasonal tourism profit.

Sustainable Economic Alternatives

To make Tanguar Haor tourism economically just and environmentally sustainable:

-

Formal Registration and Regulation of all houseboats is essential. This will help enforce pollution controls and tax compliance.

-

Eco-friendly Infrastructure Development—such as locally owned guesthouses, floating restaurants using proper sanitation, and community-run tour services—can offer tourists a rich experience while involving locals in the economic chain.

-

Revenue Sharing Models must be introduced where a portion of tourism income is reinvested into local environmental protection, waste management, and livelihood programs.

-

Skills Development Programs for local youth can build a stronger service economy that replaces harmful exploitation with innovation and sustainability.

Read More: Global Fuel Prices Spike Amid Middle East Tensions

Our Responsibility to Tanguar Haor’s Water: A Call to Protect Our Own Living Wetland

Tanguar Haor is not just water spread across a floodplain. It’s a living, breathing ecosystem one that once thrived with native fish, rare birds, and vibrant aquatic life.

For generations, it has been a lifeline for thousands of families who depend on its water for fishing, farming, and daily survival. Today, it stands at a crossroads between life and loss.

As pollution spreads, illegal fishing continues, and harmful human activities like unregulated tourism and dumping of waste go unchecked, the water of Tanguar Haor is losing its purity, its depth, and its soul. The clear water that once reflected the sky is now struggling to reflect the life it once held.

So, what is our responsibility?

We owe it to Tanguar Haor to:

-

Stop pollution at its source—Every piece of plastic, every drop of oil, every chemical dumped into the haor waters is a wound to its body. Local tourists, visitors, boat operators, and nearby communities must be educated and regulated to keep the water clean.

-

Say no to destructive fishing practices—Banning harmful nets like China Duari and electric fishing is not just about fish—it’s about protecting entire species that are silently disappearing.

-

Support sustainable tourism—Floating houseboats with loud music and waste disposal must be regulated. Tourism must serve the haor, not destroy it. Eco-friendly, guided tourism that respects nature can generate income without destruction.

-

Join hands with local people—No conservation project can succeed unless the people of the haor are involved. The water belongs to them, and they must be the first protectors and beneficiaries of its restoration.

-

Respect the seasonal rhythm of the haor—Tanguar Haor has its own life cycle. Respecting the breeding season of fish, the nesting season of birds, and avoiding excessive disturbance during these times is crucial.

It’s not too late. If we want our future generations to see the Tanguar Haor we once knew to see fish darting through water, to hear the call of migratory birds, to witness the gentle sway of aquatic plants we must act now.

Protecting Tanguar Haor’s water is not just a job for the government or NGOs. It’s a duty we all share locals, tourists, citizens, policymakers. Every drop of clean water preserved is a step toward healing this majestic wetland. Let Tanguar Haor flow freely again not just with water, but with life.

References:

Prothom Alo, Voice 7 News, UNDP

Share via: